In previous posts, I covered the latest data for weekly Covid19 pandemic dynamics for:

- Global data and trends: https://trueeconomics.blogspot.com/2021/02/14221-covid19-update-worldwide-data.html;

- European & EU27 data and trends: https://trueeconomics.blogspot.com/2021/02/14221-covid19-update-europe-and-eu27.html;

- Data and trends for the most impacted countries and regions: https://trueeconomics.blogspot.com/2021/02/14221-covid19-update-most-impacted.html; and

- Data on COVID19 dynamics in BRIICS countries: https://trueeconomics.blogspot.com/2021/02/14221-covid19-update-briics.html.

Now, as usual, EU27 (and Europe) comparatives to the U.S.

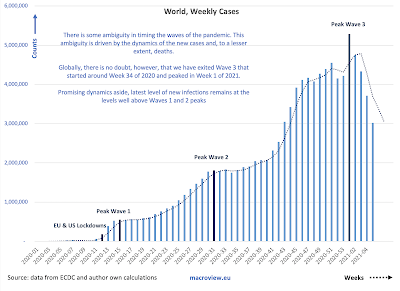

Start with new cases (weekly totals):

Since the start of the pandemic, the U.S. has experienced three waves, against the EU27's two. The EU27's 2nd wave appears to have crested in week 45 of 2020, while the U.S.' current wave continued to rise until Week 1 of 2021. Over the last 8 weeks, US new cases exceeded those in the EU27 by 3,574,708 and population-size adjusted deaths by 29,150.

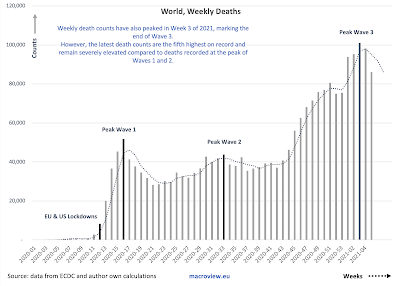

Next, weekly deaths:

The EU27's 2nd wave appears to have crested in week 48 of 2020 in terms of deaths, while the U.S.' current, third, wave continued to rise through week 3 of 2021. The EU27 weekly deaths counts show little signs of significant moderation since the Wave 2 peak, however, and are still running above Wave 1 peak.

Neither the U.S., nor the EU27 show any significant signs of deaths moderation that can be expected to occur in line with decline in new cases and vaccinations. This is surprising, because EU27 new cases moderated substantially since the peak of Wave 2.

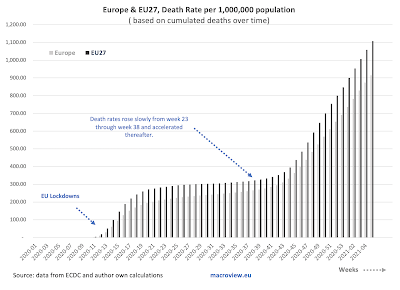

Cumulated deaths per capita:

Since the start of Wave 2 in the EU27 (Wave 3 in the U.S.), EU27 deaths per capita have been converging with those in the U.S.

At the start of the EU27 Wave 2, U.S. total deaths per capita exceeded those in the EU27 by 87%. In week 5 of 2021, excess U.S. deaths compared to the EU27, cumulated over the period of pandemic stood at 96,595, or 108,1787 on the age-adjusted basis.

In other words, U.S. cumulated deaths now exceed those in EU27 by 20.8 percent on population-size adjusted basis and by 23.3%.

U.S. excess mortality compared to the EU27 and Europe, once we account for population differences is still rising:

In highly simplified terms, the U.S. pandemic experience has been associated with a cumulative excess mortality, compared to the EU27 and Europe of between 96,595 and 160,584 cases, respectively, based solely on differences in population sizes.

If older European and EU27 demographics are factored in, these excess U.S. deaths rise to 108,200 and 134,800, respectively.

I recently covered some new research on the policy-level failures in the U.S. during the COVID19 pandemic (see https://trueeconomics.blogspot.com/2021/02/3221-cost-of-trumps-failures-to-act-on.html). In simplified terms, the numbers above are shocking: were the U.S. to match policy responses in the EU27, we could have expected a death toll 96,600-108,200 lower than we currently observe.

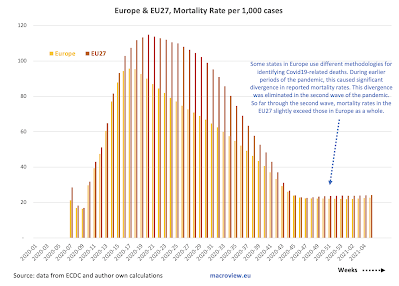

The U.S., however, managed much better than the EU27 in terms of deaths per case or the morbidity rate of the disease:

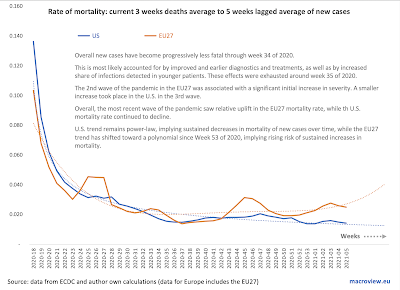

Overall new cases have become progressively less fatal through week 34 of 2020. This is most likely accounted for by improved and earlier diagnostics and treatments, as well as by increased share of infections detected in younger patients. These effects were exhausted around week 35 of 2020.

The 2nd wave of the pandemic in the EU27 was associated with a significant initial increase in severity. A smaller increase took place in the U.S. in the 3rd wave. Overall, the most recent wave of the pandemic saw relative uplift in the EU27 mortality rate, while the U.S. mortality rate continued to decline.

U.S. trend remains power-law, implying sustained decreases in mortality of new cases over time, while the EU27 trend has shifted toward a polynomial since Week 53 of 2020, implying rising risk of sustained increases in mortality.

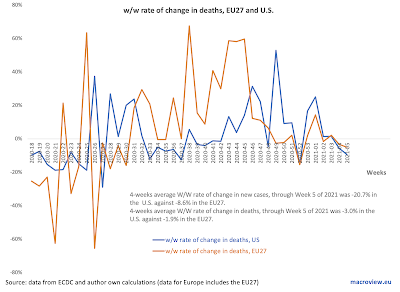

In terms of the rate of change in weekly deaths:

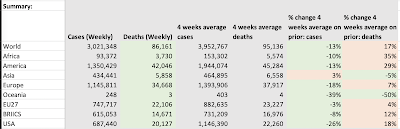

4-weeks average W/W rate of change in new cases, through Week 5 of 2021 was -20.7% in the U.S. against -8.6% in the EU27. 4-weeks average W/W rate of change in deaths, through Week 5 of 2021 was -3.0% in the U.S. against -1.9% in the EU27.

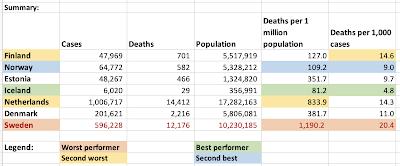

A summary of the U.S.-EU27 comparatives: