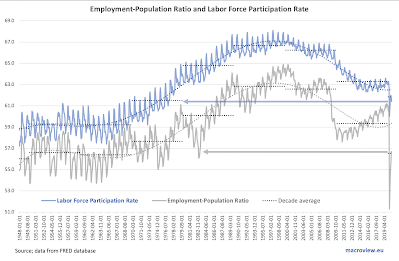

In the previous post, I covered U.S. continued unemployment claims: https://trueeconomics.blogspot.com/2021/04/2421-us-continued-unemployment-claims.html, noting that decreases in unemployment counts are, in part, driven by workers dropping off unemployment rolls due to exits from the workforce and/or expirations of unemployment benefits. Here is the data on U.S. labor force participation rates and employment to population ratio through March 2021:

Things are still ugly when it comes to these two measures of labor markets health in the U.S:

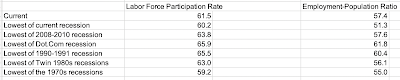

- Latest reading for U.S. labor force participation rate at 61.5 is just a notch up on February's 61.3, but is unchanged on November 2020. Pandemic period average labor force participation rate is woefully low at 61.7, which is still higher than March 2021 reading. March reading is equivalent to the average reading for the decade of the 1970s which was marked by stagflation and high unemployment.

- Latest reading for U.S. employment to population ratio is at 57.7 - an improvement on February reading of 57.3, and better than the pandemic period average of 56.9, but still comparable to the levels seen only in the early 1980s.