There has been quite a puzzling development in recent years in the monetary policy universe. A decade plus of ultra low interest rates has been associated with rising, not falling, risk premium in investment markets. In other words, a dramatically lower cost of new and carried debt induced by lower interest rates - a driver for lower risk, is being offset by something else. What?

Laine, Olli-Matti paper "Monetary Policy and Stock Market Valuation" (September 18, 2020, Bank of Finland Research Discussion Paper No. 16/2020: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3764721) tries to explain.

To start with, some theory - especially for my students in the Investment and Financial Systems courses. Per author, "the value of a stock is the present value of its expected future dividends... Hence, the changes in stock prices must be explained by

- either changes in dividend expectations or

- changes in discount rates.

The discount rate, or (approximately) expected rate of return, can be thought as a sum of a risk-free rate and a risk premium. Theoretically, monetary policy should have an effect on stock prices through the risk-free rates. In addition, monetary policy should affect dividend expectations, for example, through the output or debt interest payments of firms. The effect on the risk premium (not to mention the term structure of risk premia), however, is less clear."

Looking at Eurostoxx50 index components, Laine shows "...that the average expected premium has increased considerably since the global financial crisis. This change is explained by the change in long-horizon expected premia. ... monetary policy easing has had a positive impact on the expected average premium."

Specifically (emphasis added): "a negative shock to the shadow rate is estimated to increase average expected premium persistently. Instead, the results show that monetary policy easing temporarily decreases short-term expected [risk] premia. This means that expansionary monetary policy steepens the slope of the term structure of risk premia."

This is not exactly new, as Bernanke and Kuttner (2005) observed that "expansionary monetary policy generates an immediate rise in equity prices followed by a period of lower-than-normal excess returns. ...However, Bernanke and Kuttner (2005) do not study the effect on the long-run excess returns. My results show that effect on long-horizon expected premia has a different sign. This effect on long-horizon premia seems to more than offset the effect on short-horizon premia."

Interestingly, "Contractionary monetary policy increases the short-term premia temporarily, but decreases long-horizon premia persistently. The effect on average expected premium is negative. Thus, monetary policy tightening actually makes stocks expensive relative to the expected stream of dividends. The results provide no evidence that expansionary monetary policy causes stock market bubbles..."

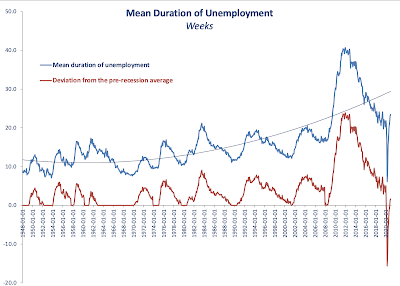

Here is (annotated by me) a chart showing evolution of implied and actual risk premia:

From theory perspective, therefore, monetary policy "can affect equity prices through the dividend expectations, expected risk-free rates or expected premia":

- "The effect of expansionary monetary policy on the dividend expectations is probably positive, because expansionary monetary policy can be expected to increase output and firms’ earnings.

- "Expansionary policy probably lowers the risk-free rates, but it is also possible that the effect is totally different. Central bank’s rate cut can increase risk-free rates, if people think that the rate cut eventually increases inflation.

- "As for the expected premium, the sign of the effect is unclear. ... Gust and López-Salido (2014) show theoretically that expansionary monetary policy lowers the premium ... where asset and goods markets are segmented. When it comes to quantitative easing, ... investors who have sold their assets to the central bank rebalance their portfolios into riskier assets, which lowers their expected returns. ... Theoretically, it is also possible to argue that monetary policy easing actually increases the expected premium. If one assumes that there exists mispricing like Galí (2014) and Galí and Gambetti (2015), then the sign of the response is ambiguous. ... This means that monetary policy easing increases the expected premium implied by dividend discount model (see Galí and Gambetti, 2015, p. 250-252)."

So, onto the empirical results by Laine:

- "Interest rates have declined considerably since the global financial crisis, yet the expected average stock market return has remained quite stable at around 9 percent. This implies that expected average stock market premium has increased remarkably. This rise is mainly explained by the premia over a discounting horizon of four years.

- "These results may seem unintuitive as the prices of stocks have risen, and ratios like price-to-earnings have been historically high. However, high price-to-earnings ratios do not necessarily mean that stocks are expensive, because the value of a stock is the present value of its expected future dividends.

- "When it comes to the role of monetary policy, the results show that monetary policy easing decreases short-horizon required premia, but increases longer-horizon premia.

- "The effect on expected average premium is positive, i.e. expansionary monetary policy lowers the prices of stocks in relation to the expected dividend stream."