This is an unedited version of my Sunday Times article from March 10.

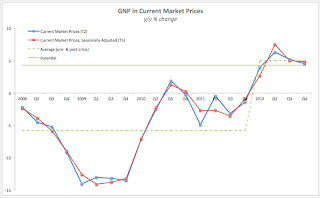

Some two years ago in these very pages, I have described the prospects for the Irish economy as following a flatline trend with occasional volatility. In other words, back in the beginning of 2010, the economy’s prospects for the near-term future were consistent with an L-shaped recovery: stabilization followed by near-zero growth.

Taking the first three quarters of 2012, in headline terms, the above prediction has translated into 2009 to 2012 GDP growth of just 0.22% per annum, GNP decline of 0.16% per annum and domestic demand drop of 4.81% per annum. Again, let’s take a look at the above numbers from a different angle. Compared to the pre-crisis levels, the latest GDP data shows that over 2011-2012, Irish economy was able to close just 22% of the gap between GDP peak and the Great Recession trough, implying that it will take Ireland through the end of 2014 before we get our GDP back to the half-point of the Great Recession. At the same time, Domestic demand continued to hit crisis period lows in 2012 and all international projections show that 2013 will be another post-2007 low for these data series.

With these rather depressing statistics in mind, one is warranted to take with a grain of salt ever-more frequent and boisterous pronouncements from the Government that Irish economy has ‘turned the corner’. Ditto for the ever-more saccharine messages from the EU policymakers to the ‘best pupil’ in their austerity policies ‘class’.

And the most recent data – through Q4 2012 and January-February 2013 – is offering no signs of any statistically significant improvements in the economy compared to the rather abysmal 2012.

Mortgages arrears were once again up in the last quarter of 2012. While the rate of increases was markedly slower than in previous quarters, number of accounts currently in arrears 21.4% year on year. As of the end of 2012, some 186,785 private residencies-related mortgages are either in arrears, in temporary restructuring or in the process of repossessions – almost 25% of all accounts outstanding if we were to use as the base total accounts numbers comparable across the 2009-2012 horizon. All in, some 650,000-700,000 Irish residents are currently under water when it comes to paying on their original mortgages. Some turnaround in the economy to witness.

Data for January-February 2013 on new cars registrations shows that not only the motor trade is continuing to suffer from on-going collapse in sales, but that there is no indication of any substantial improvement in either the Irish households or the Irish SMEs outlook for the future. New private cars registrations are down 20% year-on-year over the first two months of 2013, while new goods vehicles registrations are down 21.4%. This shows clearly that Irish consumers are not engaged in purchasing large-ticket items and, supported by the declines in durable goods consumption evident in the retail sales data, signals that consumers have little real credence in the ‘green shoots’ theory espoused by our Government officials and business leaders. Lack of demand uplift in goods vehicles, on the other hand, shows that when it comes to capital investment, Irish businesses are also refusing to buy the hype of economic turnaround. In any cyclical recovery, capital expenditure, especially on rapidly depreciating items such as vehicles used in transporting goods for wholesale and retail trade, logistics and transportation services, is one of the leading indicators of improving economic conditions. Data for the first two months of this year shows no such uplift.

Core retail sales, once stripping out motor sales, are showing a slightly more upbeat activity. While all retail business activity has declined on average over 3 months through January 2013 compared to year ago, some encouraging signs of uplift were present in the Department Stores sales, and sales of electrical goods when it comes to volume and value of sales. Nonetheless, two factors continue to characterize Irish domestic consumption: extremely low activity from which any increases might take place, and exceptionally anemic trend in any rises we do record.

On the investment front, gross domestic capital investment remained basically unchanged in the first 3 quarters of 2012 compared to 2011,ann there are currently no signs that this situation has changed since the end of Q3 2012. We are now into the fourth consecutive year of gross investment failing to cover amortisation and depreciation of the capital stock accumulated over the years of the Celtic Tiger. Recalling that our growth success over 1992-1998 was predicated on a rapid catching up in capital stock and quality relative to our, at the time more prosperous European partners, this means that the ongoing crisis is effectively erasing any capital gains achieved post 1999.

In short, domestic side of the economy shows no green shoots of any harvestable variety. And the potential headwinds we are likely to face in the near-term future are still severe.

In property markets and when it comes to mortgages arrears, we face a long list of risks that are yet to play out. Impacts of property taxes introduced in the Budget 2013, the upcoming lifting of the banking guarantees, and the saga of the Personal Insolvency regime reforms all represent distinct threats to the fragile stabilisations achieved in these areas of the economy.

On business investment front risks are also mounting, rather than abating. Continued lack of bank credit and strong indications that in the near term Irish banks are likely to follow their other Euro area counterparts in dramatically hiking the retail interest rates for both existent and new loans.

When it comes to consumers’ appetite for spending, latest consumer confidence data shows significant deterioration in confidence in February, compared to January 2013 and to 2012 average. If anything, when it comes to consumers’ reported outlook for 2013, things are getting worse relative to 2012, rather than better.

Which leaves us with the Government’s old favorite signal of the recovery: Irish exports. The hype about Irish external trade prowess is such, that even a usually somber IMF has recently waded in with a lengthy paper outlining how Ireland is likely to turn back to Celtic Tiger era prosperity on foot of booming exports. In summary, the IMF missive, titled Boosting Competitiveness to Grow Out of Debt – Can Ireland Find a Way Back to Its Future concluded that “Ireland is poised to return to its path of strong growth and low imbalances” on foot of “enhanced competitiveness”.

The idea that ‘exports-led recovery’ is Ireland’s only salvation from the systemic and structural crises we face is not new. Previous Government put as much credence into this proposition as the current one. Alas, this idea – as I have pointed out repeatedly – is simply not reflected in the reality of the Irish economy for a number of reasons.

It is true that Irish exports growth has improved significantly during 2009-2012 period, rising from negative 3.75% in 2009 to a positive 6.25% in 2010 and 5% in 2011. In the first three quarters of 2012, exports of goods and services were up 6.8% on the same period of 2011.

Alas, the composition of our exports has shifted dramatically toward more services exports, as opposed to goods exports. In addition to reducing the overall level of real economic activity and employment associated with every euro worth of exports, this shift also has meant a number of changes that further divorce our external trade activity from economy. Firstly, most of employment creation in the exports-oriented services sectors, such as International Finance and ICT services, is oriented toward specialist, highly educated foreign employees, instead of domestic unemployed or underemployed individuals. Secondly, services exports are associated with greater cost (or imports) intensities as they require higher payments for patents and intellectual property, which are neither taxed in Ireland, nor are developed here. This means that while exports of services generate high revenues, much of these revenues is not captured within our economy. Thirdly, exports of services, as opposed to exports of goods, are more concentrated in a handful of giant MNCs. This fact, known as the ‘Google effect’ drives up the cost of hiring skilled workers for Irish SMEs, reduces margins at Irish enterprises, lowers investment into Irish SMEs, and actually undermines our competitiveness, rather than improving it.

In short, booming exports along the current trend can actually cost this economy its ability to sustain indigenous entrepreneurship and investment in the long run. Instead of supporting growth and recovery, the green shoots of some of our exporting activities can turn out to be super-strong weeds of the economy suffering from a classical Dutch disease where resources flow to an increasingly inefficient use in specialist sectors, exposing the society and the economy at large to future adverse shocks.

Lastly, as with other indicators, the latest data, covering only goods exports, shows that our external trade is suffering from a significant slowdown in global demand and the pharmaceutical sector patent cliff. Once again, I warned about both of these factors more than a year ago.

At the same time, on the more positive note, the ongoing US and global economic recovery should provide some support for goods exports from Ireland, especially in the areas relating to capital investment goods and equipment in months ahead.

In short, the miracle of the ‘exports-led recovery’ is simply nowhere to be seen at this point in time, despite the fact that exporting activity continues to expand and despite the fact that this activity represents the only bright spot on our economic horizon.

After five years of the greatest economic crisis in the modern history of this nation, it is time to ask our political leaders a question: at what point in time does one’s rhetoric of economic turnarounds becomes an unbearable burden to one’s political and social reputation? For the previous Government it took just under 3 years to face the music of its own making. For this Government, the clock is ticking on.

Box-out:

Having achieved a relatively underwhelming progress on restructuring the Promissory Notes of the IBRC, the Government has turned its attention in recent weeks on attempting to restructure our debts to the European sides of the Troika. However, the issue of the Promissory Notes is still an open topic. Last week at a conference in Brussels I had a chance to speak to some senior decision makers from the European Parliament and the EU Commission who unanimously voiced their concern over the potential for the ECB to alter the terms and conditions of the Irish Promissory Notes restructuring deal. ECB has two material powers to do so. Firstly, it can simply alter by a majority decision the technical aspects of the deal. Secondly, the ECB has the ultimate power to determine the overall schedule of the sales of the long-term bonds issued to replace the Promissory Notes to the private investors. This latter power is very significant. Under the current arrangement, the Central Bank of Ireland has committed to an annual schedule of minimum disposals of bonds. Based on this schedule, the cumulative long-term benefit of the deal to Ireland can be estimated in the range of Euro 4.5-6.3 billion over the 40 years horizon. Accelerating the rate of disposals by a third on average over the deal horizon can see the net gains to the Exchequer declining by more than a quarter. Hardly a confidence-inspiring outcome for the Government that put so much hype behind the deal.