For those impatient - there is an estimate of Ireland Inc debt at the bottom... that can be compared with the US debt...

What is going on with the US economy? I expected the figures coming out on economic front (and earnings front outside the Federally financed banks) to be bad, but today's numbers are poor by all measures. According to the Fed's Conference Board, the index of leading economic indicators fell 0.3% in March, after a dip of 0.2% in February (revised up). But decomposition is telling:

- Building permits were the largest negative contributor in March, as builder have finally started to cut production in honest - much of this backed by the decreases in new starts, as finance committed to projects in 2008, signed for in 2007, has dried up. This is a welcome sign, as outstanding stock of unsold houses has to be pared back before any real recovery (as opposed to cliff-and-bottom bouncing) takes place.

- Stock prices, and the index of supplier deliveries also registered large negative contributions to the index in March, showing that real activity is continuing to deteriorate at, seasonally significantly faster rate. There is no spring bounce for now, and these are leading indicators, suggesting that any recovery upwards will require some new alchemy from the White House and the Fed.

- The real money supply was the largest positive contributor as the Feds printing presses were working overnight amidst deflation. And another sizeable positive push came from the yield spread - a sign that some of the future support might be waning - yield spreads narrowing is underpinned by lower Fed rates (not by healthier financial system, for banks are continuing to drop dead at an accelerating rate - 25 as of today in 2009 alone, and counting). So as the Fed has run out of options (short of setting negative nominal rates - e.g issuing loans with a principal repayment at a discount to the face value of the issued loan) and spreads are likely to start widening into the future as: (a) Uncle Sam's borrowing will remain buyoant, (b) debt refinancing will run rampant, and (c) Fed's helicopter drops of money thin out.

"There have been some intermittent signs of improvement in the economy in April," per Ken Goldstein, economist at the Conference Board. Overall, six of the 10 indicators were negative contributors, three were positive, and one was steady. Say what, Ken? Picture below is a telling one:

What Ken-omist from the Fed is referring to is the renewed momentum in the deterioration of the Leading Econ Indicators index that started in December (after a short 1-month flat) and has been going steady through March. The index has failed to bounce up in consecutive 9 months. Current Economic Conditions index is now converging downward to LEI, suggesting that unless things improve significantly in the next couple of months, simple psychology of the markets will lead to a renewed push down on LEI (the vicious cycle of self-fulfilling prophecies might commence).

Overall, in the six months to April 1, the index fell 2.5%, it declined 1.4% in the previous six months before that.

So about the only thing positive I can report has nothing to do with the Fed's own indicators, but with the decline in the new unemployment claims reported last week. If the decline persists for the next 6 weeks or so, then using comparisons with the last 6 recessions, we are at the point of inflection in economic recovery sometime now. But it is a big if, since the series can be reasonably volatile and their deviations from the monthly moving average can be significant (see

here).

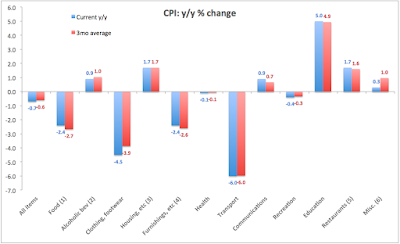

And here is a good chart on inflation expectations for the US (from the Fed:

here) - care to argue this? or shall we start taking pressure on commodities-linked stuff in preparation for the new 2% inflation bout?

Paul Krugman on Ireland today: a good one from Krugman here. But an even better one from a comment to his article by PMD: "...Krugman and most of our own home-grown economists appear to regard cuts in public spending as being the same as tax increases. They have a model in their head with credit and debit on two sides and they are studiously agnostic about how the government should go about balancing the books. Those of us who work in the real economy know that increasing taxes on the productive part the economy - and that's 'productive' as in 'productivity' as in the only way to generate real wealth as in the only way to escape recession / depression - will dampen its productivity and, therefore, harm its capacity to generate wealth in the future - i.e. escape recession. All this 'sharing the pain' talk is just code for: we'll confiscate private sector wealth in order to avoid reform in the public sector. You can imagine a rich Titanic passenger on a half empty lifeboat blowing his nail and calling out to a dying pleb in the sea 'Chilly for this time of year. Isn't it?' I profoundly disagree with the reversion to the cargo cult school of economic management: let rich foreigners turn up and employ us. What on earth do we pay these mandarins for if the best they can come up with is 'something will turn up'? There are core domestic issues of productivity that are not being addressed." I couldn't have put it any better than this myself!

Lorenzo 'the Not-so-Magnificent' Smaghi... (or should it be Maghi?) is ECB's latest loose cannon... In an interview with FT Deutschland, Lorenzo Bini Smaghi of the ECB predicted that the Euro-zone recovery will follow the mirror image of a J-curve – a shallow recovery after the fall. Ok, I agree with this. In fact, I have warned for some months now that any recovery in the Euro-zone and Ireland in particular will be shallow and slow and will leave the continent at the trend growth rate of below 0.75% GDP, with Ireland at below 1% GDP pa. ECB's latest would-be-forecaster also 'predicted' a persistent and significant fall in potential growth rates going forward. Another thing Smaghi went into is inflation expectations: "'Inflation expectations are moving upwards (in euro area, U.S. and U.K.); no expectations of deflation," said the text of his presentation. Again, another theme I've been hammering about for some time now.

But... (S)maghi appeared to suggest that

non-conventional monetary policy action would be likely soon, without giving any details. What this might be? Negative

nominal interest rates? Unlikely. A policy of accepting all and any bonds issued by the member states? Brian Lenihan can wish... It is all but inevitable that the ECB will have to rescue Ireland and some of the other APIIGS. Such a rescue will have to be

unconventional and not only because there is no existent convention within the Euro framework for doing so, but because as Smaghi stated in his presentation, households across Europe have lost faith in sustainability of public finances and have started to hoard cash. Nowhere more apparent than in Ireland. After surviving through a decade of anaemic (embarrassingly low, by some standards) economic growth, this is the second greatest threat point for the Euro.

A pat on the back: A stoodgy, but occasionally interesting quasi-official Euro economics website/blog: EuroIntelligence.com has the following 'news' item today. A long recession, a shallow recovery: The IMF has prereleased chapters 3 and 4 of its WEO. This is from the introduction of

chapter 3 “…recessions associated with financial crises tend to be unusually severe and their recoveries typically slow. Similarly, globally synchronized recessions are often long and deep, and recoveries from these recessions are generally weak. Countercyclical monetary policy can help shorten recessions, but its effectiveness is limited in financial crises. By contrast, expansionary fiscal policy seems particularly effective in shortening recessions associated with financial crises and boosting recoveries. However, its effectiveness is a decreasing function of the level of public debt. These findings suggest the current recession is likely to be unusually long and severe and the recovery sluggish.”

Imagine this! See here for March 3 post that uses the exact precursor to Chapter 3 release... Oh dear, sometimes it is worth checking if a 'new' release is actually 'news'...

ESB's disgraceful entry into 'stimulus' economics has moved on to the next stage. As I noted in two earlier notes, the ESB plan for 'jobs creation' is an affront to the idea of competition and consumer interests (here), as well as an insensitive move at the time of economic hardship for many (here). Now, as today's IT reports (here) we are also looking at more Georgian Dublin demolitions... Is this predatory and arrogant monopoly ever going to brought under normal market controls? And is Irish Times ever going to become a paper where journalism stops being platitudinous to state monopolies and all-and-any 'Green' / 'sustainable' labels and starts seeing the likes of ESB for what they really are? And per wages and earnings in ESB... well, indeed in the entire public sector, see this excellent blog post from Ronan Lyons here. A must read.

A late Sunday thought - with Obamamama economics, how much debt is the US economy carrying?

Well, there are many sources of debt:

- National debt = currently at $11.2 trillion (per US National Debt Clock calculator here);

- Federal bailout commitments = so far set at $12.8 trillion (up from $4 trillion left by the previous Administration, per March 30 report by Bloomberg here);

- Federal entitlements commitments under Medicare and Social Security obligations = $52 trillion in current debt from the Federal Government to the system or $117 trillion in the present value of unfunded obligations (per National Center for Policy Analysis, as of December 2009, here);

- Private sector corporate and financial liabilities = $17 trillion (per US Federal Reserve numbers of December 2008, here)

- Private households liabilities $13.8 trillion (ditto), mortgages $10.5 trillion (here and a breakdown here) = $24.8 trillion.

Total = $117.8 - 172.8 trillion or 829.6-1,217% of 2008 GDP!

Financed at the current 30-year US Treasury rate of 3.79%, the interest payment on this debt alone will be $4,465-6,549 bln per annum - up to 46.1% of the country annual GDP.

We are not considering the pesky issue of the derivative instruments issued within the US system. These are notional debts, but they can come back and bite you as well. Per the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (

here), as of the end of Q4 2008 US held:

- interest rate derivatives to the tune of $164 trillion;

- CDS at $15.9 trillion,

- other stuff: FX, equities, commodities -based derivatives, to the total of $20.5 trillion

So

Derivatives grand total of

$200.4 trillion.

Which brings

US total debt obligations to

$318.2-373.2 trillion = upwards of 2,628% of US GDP!Considering that the US current population is

306,251,267, the total

US debt per capita is between $1.31mln and $1.22mln, with a

servicing cost of up to

$46,185 per annum per person!And amidst this, Obama is talking traditional Democratic drivel of 'spending the economy out of a recession'? While Paul Krugman is wailing that not enough is being spent?

Can anyone really doubt that inflation is around the corner? If so, consider the above figures and do tell me how can the US get out of this corner without a massive debt write-off via inflation and sustained devaluation? Dollar at 1.75 to the Euro in two years time and interest rates in double digits?

Now on to Ireland Inc's debt:

- National debt = currently at €54.245bn (per NTMA here);

- Government bailout commitments = so far set at €400bn (here) under Banks Guarantee Scheme, €70bn (my estimate in the forthcoming B&F article) under NAMA, €87bn (here); Sub-total = €557bn;

- Public entitlements commitments under Pensions, Social Welfare and Health obligations = €75bn (Pensions: here), €66.3bn (€38bn per annum spending on health, wages & social welfare taken over 30 years horizon with deficit of 10% per annum over term) in the present value of unfunded obligations; Sub-total = €141.6bn;

- Private sector corporate and financial liabilities = Monetary Financial Institutions: €810bn, inc of IFSC, corporate sectors: €551bn; Direct Investment: €183.6bn (here); Sub-total = €1,544.6bn

- Private households liabilities (per my earlier estimates here) = €150bn.

Total = €2.45 trillion or 1,440% of 2009 GDP!

Financed at the current 5-year rate over 30 year horizon (roll-over) of 4.5%, the interest payment on this debt alone will be €110.25bn per annum - up to 64.9% of the country annual GDP. Put differently - the debt/liabilities of this economy are currently amounting to ca €555,048 per every person living in Ireland...