This is an unedited version of my article for Sunday Times, March 24.

This week, euro area leaders have added yet another term to the already rich vocabulary engendered by the financial crisis. If only a few days ago the world was divided into too-big-to-fail (e.g. Irish pillar banks and Spain) and too-big-to-bail (e.g. Italy) institutions and economies, today we also have too-small-to-fail and too-small-to-bail economy, Cyprus.

Worth just 0.2% of the euro area GDP, with the insolvent banking sector and the liquidity strained sovereign, Cyprus is a tiny minnow in terms of both the required external assistance and its direct impact on the euro area economy. The country overall GDP amounts to about ½ of the cost of bailing out Anglo Irish Bank, and its banking and fiscal troubles need just EUR15.8 billion of funding to plug the gap left by the EU mishandling of the Greek bailout back in 2011-2012. With the reputational costs to the euro area of letting this nation go into an unassisted default, Cyprus is simply too-small-to-fail.

Despite this, the end game now being played in Nicosia, Moscow, Frankfurt and Berlin shows that Cyprus, perhaps, is also too-small-to-bail. The problem is that granting sufficient funding to Cyprus via Troika loans risks pushing the Cypriot Government debt/GDP ratio to 170% even with the haircut on depositors. Were the EU adhere to the conditions of the bailout that also envision Cypriot banking and financial services sectors shrinking to euro area average in size, the government debt to GDP ratio can reach above 210 percent. Yet, altering the terms of the bailout to provide funds that are not debt-based, such as directly funding the banks writedowns of Greek Government bonds, risks triggering calls for similar actions across the rest of the euro area periphery. Pretty quickly, Cypriot EUR10 billion bill can swell to EUR200-250 billion call on the ECB.

These dilemmas, yet to be fully articulated by the policymakers publicly, are nonetheless informing the mess behind the recent events. In the view of euro area leadership, dealing with Cyprus either requires bankrupting its economy and its people, or risking destroying the monetary system infrastructure that rests on the ECB’s pursuit of singular, deeply flawed, yet legally unalterable mandate. A familiar conundrum that has been played out in Ireland, Greece, Portugal and Spain by the incompetent crisis management from Brussels, Frankfurt and Berlin.

Alas, what is still missing in the Cypriot Dilemma debates is the consideration of the longer-term impact of this latest iteration in the euro area crisis on broader European economy.

In this context, Cyprus is neither too-small-to-bail, nor too-small-to-fail. Instead, it is a systemically important focal point of the euro area financial crisis.

The Cypriot crisis orderly resolution requires funding from some non-debt sources to plug the gap between EUR17 billion in funds needed and EUR10 billion that can be committed in the form of loans. The EU has opted to bridge this gap with a levy on the deposits, thus triggering a wholesale expropriation of private property without any legal basis for doing so. This expropriation, termed in the language resembling Orwell’s “1984” “an upfront one-off stability levy”, also cuts through the allegedly inviolable State Guarantee on all deposits under EUR100,000.

As the result, since last weekend all European and foreign depositors in the EU banks are no longer treated either pari passu or senior to risk investors, such as bondholders, but subordinated to them. Safety of deposits is no longer assured by the banking system or by the Sovereign guarantees. One of the cornerstones of the yet-to-be-established European Banking Union - the joint system of deposits insurance protection – is no more a credible mechanism of protection of ordinary savers.

In the short run, as highlighted in the media during the week, this means potential for bank runs in Greece (where depositors are already facing substantial potential losses through their savings in Cypriot banks and the state finances are in a much worse state than they are in Cyprus), Spain (with the Government desperate to fund its fiscal adjustments amidst rising tide of discontent with austerity measures) or even Italy (where savings in form of bank deposits are the main pillar of pensions provision for the aging population). In Cyprus itself, the debacle of the European leadership crisis management approach is now leading to the growing risk of the country being forced to exit the euro area.

In my view, these are low probability, but high impact risks that must be considered simply for the devastating effect they would have on the rest of the euro system.

Even if the above short-term nightmare scenarios do not play out, the Cypriot Dilemma is not going away.

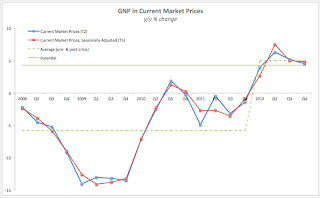

Throughout the crisis, the EU has adopted a ‘muddle-through’ approach to dealing with the problems. This has meant that instead of using aggressive monetary policy, as the US and the UK, in addressing the crisis, the EU used debt tools to plug the financing gaps in the banking and fiscal sectors. The result of this was a dramatic uplift in overall debt burdens. While euro area General Government deficit is expected to reach a relatively benign 2.56% in 2013 with a primary balance (excluding debt financing costs) forecast to post a surplus of 0.25%, close to the pre-crisis 2008 levels, euro area government debt is expected to rise from 70% of GDP in 2008 to 95% this year. Deficits are down, debt is up, public and private investment and deleveraging running at negative or zero rates. These dynamics clearly show the true cost of the EU leadership crisis.

In the long run, Cyprus blunder is going to yield dramatic economic and social costs.

Firstly, any resolution of the Cypriot crisis will involve unsustainable debt for the Government and the wholesale destruction of the Cypriot economy. With EU-demanded scaling back of the banking sector on the island to the ‘euro area average’, Nicosia is facing an outright contraction in the nation GDP of some 15-17% on pre-crisis levels. Second-order effects of this measure and the increase in the island corporation tax rate also demanded by Brussels will take economic losses closer to a quarter of the national income. There are no potential sources for plugging this economic hole. Even the promises of the off-shore gas reserves will not deliver economic recovery to the society with effectively no oil and gas expertise, skills or firms present in the economy.

The EU is de facto sealing the fate of one of its members as the second-class state within the Union just as it did with the rest of the ‘periphery’.

Long-term impact of debt accumulation as the sole mechanism for dealing with the crisis will also hit the entire euro area. Per IMF relatively benign projections, euro area combined debt to GDP ratio will now exceed or equal 90% bound for at least six years in a row. This means that the euro area is facing a debt overhang crisis of the size where Government debt levels impose a long-term drag on overall economic growth. Any adverse headwinds to economic growth and fiscal performance in years to come will have to be faced without a cushion allowing for fiscal policy accommodation.

Undermining of the sovereign guarantees and depositors’ protection principles in the Cypriot case, even if reversed in the final agreement, will also have a long-term effect on euro area growth potential. With savings no longer secured from expropriation, euro area is facing long-term realignment of the household investment portfolios. This realignment will reduce bank deposits, especially the more stable termed deposits, and lower euro area assets held by the households. The end result will be higher cost of bank credit and equity in Europe, smaller supply of loanable and investable funds and, thus, lower long-term investment activity.

Violation of the property rights and trampling upon the principles of the common market in structuring of the original Cyprus ‘rescue’ plan means that overall risk-return valuations by investors will be re-adjusted to reflect the state of policymaking in Europe that puts bondholders over all other financial system participants, including, now, the depositors.

Currently, euro area economic activity and investment are funded primarily via bank credit, reliant on deposits and bank capital. Shares and equity account for around 14.3% of the total household portoflios in Europe as contrasted by 32.9% in the US. In order to rebalance the euro area investment markets away from reliance on more expensive and risk-prone bank lending, the EU must incentivize equity holdings over debt and shift more of the banks funding activity toward more stable deposits, reducing the amount of leverage allowed within the system. Cypriot precedent makes structural change away from debt financing much harder to achieve.

Lastly, the Cypriot crisis has contributed to the continued process of deligitimisation of the EU authorities in the eyes of European people who witnessed an entirely new and ever more egregious level of the first-tier Europe (the so-called ‘core’) diktat over the social and economic policies in the peripheral state.

Prior to last week, Cyprus might have been too-small-to-fail or too-small-to-bail from Frankfurt’s or Berlin’s perspective, however the way the EU has dealt with this crisis exposes systemic flaws in the political economy of the euro area that cannot be easily repaired and will end up costing dearly to the entire EU economy.

Box-out:

The revenue commissioners annual statistics data for 2011 throws some interesting comparisons. Back in 2010, prior to the more recent increases in income-related levies and charges, gross taxable personal income in Ireland amounted to EUR77.7 billion against the taxable corporate income of EUR70.8 billion. The amounts of income and corporate taxes paid on these were, respectively EUR9.82 billion and EUR4.25 billion, yielding effective economy-wide rates of tax of 12.6% for personal income and 6.0% for corporate tax. Thus, excluding USC, PRSI, most of Vat, and a host of other taxes and charges applicable uniquely to households, Irish Government policy is explicitly to tax personal income at an effective rate of more than twice the rate of corporate income. Of course, this disparity in taxation is inversely correlated with the disparity in representation: when was the last time you heard our leaders talk about not increasing tax burden on people as a sacrosanct principle of the state in the same way they talk about protecting our corporation tax regime?