My article for The Currency on the German Constitutional Court ruling regarding ECB's PSPP program: https://www.thecurrency.news/articles/17028/german-courts-are-fighting-with-the-ecb-what-does-it-mean-for-ireland.

Showing posts with label Government bonds. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Government bonds. Show all posts

Tuesday, May 19, 2020

19/5/20: German Hawks vs ECB Doves?

My article for The Currency on the German Constitutional Court ruling regarding ECB's PSPP program: https://www.thecurrency.news/articles/17028/german-courts-are-fighting-with-the-ecb-what-does-it-mean-for-ireland.

Wednesday, July 31, 2019

Tuesday, July 16, 2019

16/7/19: Corporate Yields are Heading South in the Euro Land

Some of the euro area's junk-rated corporate debt is now trading at negative yields, and over 15% of near-junk debt is also charging the lenders to provide cash to financially weaker companies:

Source: WSJ

While the overall stock of negative yielding debt (sovereign and corporate) is now nearing $13.5 trillion worldwide:

Source: Bloomberg

All in 51 percent of all European Government bonds are trading at negative yields, and just over 30 percent of all investment grade corporate bond issued in Euro.

The percentage of negative yielding debt amongst junk-rated corporates is small. Bank of America ML estimated that the percentage of BB-rated European corporate bonds with negative yield rose from 0.225% at the end of May to 1.5% at the end of June. Back then, 14 companies had junk-rated bonds rated BB or lower with negative yields, with total market value of $3 billion.

The chart below plots corporate junk-rated bond yields index for the euro issuers:

Meanwhile, Greek Government bonds auction this week went into a massive demand overdrive. Greece sold more than EUR13 billion worth of 7-year bonds, almost EUR11 billion more than it planned originally, at the yields of 1.9 percent, or 2.4 percentage points above the Eurozone benchmark average. The spread to Eurozone benchmark has now fallen from 3.73 percent in March sale. In fact, U.S. 7 year bonds are selling at a yield of 1.97 percent, implying lower yields for Greek debt than the U.S. debt.

Here is the chart plotting Euro area sovereign yield curves for AAA-rated and for all bonds:

The yields on AAA-rated debt are negative out to 13 years maturity, and for all bonds to 8 years maturity.

Wednesday, June 12, 2019

12/6/19: All's Well in the Euro Paradise

All is well in the Euro [economy] Paradise...

Via @FT, Germany's latest 10 year bunds auction got off a great start as "the country auctioned 10-year Bunds at a yield of minus 0.24 per cent, according to Germany’s finance agency. The yield was well below the minus 0.07 per cent at the previous 10-year auction in late May. The previous trough of minus 0.11 per cent was recorded in 2016. Notably, demand in Wednesday’s auction was the weakest since late January, with investors placing bids for 1.6-times more than the €22bn that was issued."

Because while the "Euro is forever", economic growth (and the possibility of monetary normalisation) is for never...

Monday, April 22, 2019

22/4/19: At the end of QE line... there is nothing but QE left...

Monetary policy 'normalization' is over, folks. The idea that the Central Banks can end - cautiously or not - the spread of negative or ultra-low (near-zero) interest rates is about as balmy as the idea that the said negative or near-zero rates do anything materially distinct from simply inflating the assets bubbles.

Behold the numbers: the stock of negative yielding Government bonds traded in the markets is now in excess of USD10 trillion, once again, for the first time since September 2017

Over the last three months, the number of European economies with negative Government yields out to 2 years maturity has ranged between 15 and 16:

More than 20 percent of total outstanding Sovereign debt traded on the global Government bond markets is now yielding less than zero.

I have covered the signals that are being sent to us by the bond markets in my most recent column at the Cayman Financial Review (https://www.caymanfinancialreview.com/2019/02/04/leveraging-up-the-global-economy/).

Sunday, September 9, 2018

9/9/18: IMF and Argentina: New Old Saga

My Twitter comments on Argentina and IMF rescue package were picked up by the folks at ZeroHedge https://www.zerohedge.com/news/2018-08-30/some-observations-argentinas-imf-sponsored-collapse

Monday, July 30, 2018

Friday, December 8, 2017

8/12/17: Happiness: Bounded and Unbounded

Why I love Twitter? Because you can have, within minutes of each other, in your tweeter stream this...

and this

That's right, folks. It's the Happiness Day: bounded at 0.2% annual rate of growth for the workers, and unbounded at USD11 trillion for the Governments. All good, right?

But of course all is good. We call the former - the 'great news' for the families, and the latter, 'savage austerity'. Which is, apparently, good for the bonds markets... no kidding. At least there isn't a bubble in wages, even though there is a bubble in bonds.

Sunday, June 11, 2017

10/6/2017: And the Ship [of Monetary Excesses] Sails On...

The happiness and the unbearable sunshine of Spring is basking the monetary dreamland of the advanced economies... Based on the latest data, world's 'leading' Central Banks continue to prime the pump, flooding the carburetor of the global markets engine with more and more fuel.

According to data collated by Yardeni Research, total asset holdings of the major Central Banks (the Fed, the ECB, the BOJ, and PBOC) have grown in April (and, judging by the preliminary data, expanded further in May):

May and April dynamics have been driven by continued aggressive build up in asset purchases by the ECB, which now surpassed both the Fed and BOJ in size of its balancesheet. In the euro area case, current 'miracle growth' cycle requires over 50% more in monetary steroids to sustain than the previous gargantuan effort to correct for the eruption of the Global Financial Crisis.

Meanwhile, the Fed has been holding the junkies on a steady supply of cash, having ramped its monetary easing earlier than the ECB and more aggressively. Still, despite the economy running on overheating (judging by official stats) jobs markets, the pride first of the Obama Administration and now of his successor, the Fed is yet to find its breath to tilt down:

Which is clearly unlike the case of their Chinese counterparts who are deploying creative monetarism to paint numbers-by-abstraction picture of its balancesheet.

To sustain the dip in its assets held line, PBOC has cut rates and dramatically reduced reserve ratio for banks.

And PBOC simultaneously expanded own lending programmes:

All in, PBOC certainly pushed some pain into the markets in recent months, but that pain is far less than the assets account dynamics suggest.

Unlike PBOC, BOJ can't figure out whether to shock the worlds Numero Uno monetary opioid addict (Japan's economy) or to appease. Tokyo re-primed its monetary pump in April and took a little of a knock down in May. Still, the most indebted economy in the advanced world still needs its Central Bank to afford its own borrowing. Which is to say, it still needs to drain future generations' resources to pay for today's retirees.

So here is the final snapshot of the 'dreamland' of global recovery:

As the chart above shows, dealing with the Global Financial Crisis (2008-2010) was cheaper, when it comes to monetary policy exertions, than dealing with the Global Recovery (2011-2013). But the Great 'Austerity' from 2014-on really made the Central Bankers' day: as Government debt across advanced economies rose, the financial markets gobbled up the surplus liquidity supplied by the Central Banks. And for all the money pumped into the bond and stock markets, for all the cash dumped into real estate and alternatives, for all the record-breaking art sales and wine auctions that this Recovery required, there is still no pulling the plug out of the monetary excesses bath.

Saturday, January 2, 2016

2/1/16: Bloomberg Guide to Markets: 2015 Summed Up

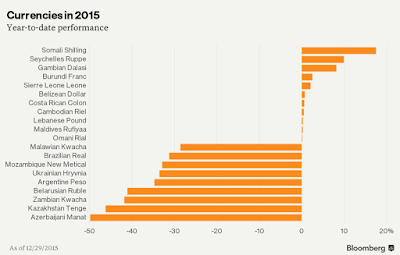

In case you want a neat (although narrow) summary of 2015 in the markets, here's one via Bloomberg:

For Equities:

For Currencies:

For Government Bonds:

And more here: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-12-31/here-are-the-best-and-worst-performing-assets-of-2015.

Tuesday, December 29, 2015

29/12/15: There Are Two Ways 2016 Can Play Out for Euro Area Bonds

With the pause in ECB QE over the holidays season, bond markets have been largely looking forward to 2016 and counting the blessings of the year past. The blessings are pretty impressive: ECB’s purchases of government bonds have driven prices up and yields down so much so that at the end of this month, yields on some USD1.68 trillion worth of Government bonds across 10 euro area countries have been pushed below zero.

Per Bloomberg chart:

Value of bonds with yields below ECB’s -0.3% deposit rate, which makes them ineligible for purchases by the ECB, is $616 billion, just shy of 10 percent of the $6.35 trillion of bonds covered by the Bloomberg Eurozone Sovereign Bond Index. As the share of the total pool of marketable European bonds, negative yield bonds amounted to more than 40% of the total across Europe at the start of December (see here: http://www.marketwatch.com/story/40-of-european-government-bonds-sport-negative-yields-and-more-may-follow-2015-12-02).

Two questions weigh on the bond markets right now:

1) Will the ECB expand the current programme? Market consensus is that it will and that the programme will run well beyond 1Q 2016 and spread to a broader range of securities; and

2) Will low inflation environment remain supportive of monetary easing? Market consensus is that it will and that inflation is unlikely to rise much above 1% in 2016.

In my view, both consensus positions are highly risky. On ECB expectations. Setting aside inflationary dynamics, ECB has continuously failed to ‘surprise’ the markets on the dovish side. Nonetheless, the markets continued to price in such a surprise throughout 2015. In other words, current pricing is probably already reflecting high probability of the QE extension/amplification. There is not much room between priced-in expectations and what ECB might/can do forward.

Beyond that, my sense is that ECB is growing weary of the QE. The hope - at the end of 2014 - was that QE will give sovereigns a chance to reform their finances and that the economies will boom on foot of cheaper funding costs. Neither has happened and, if anything, public finances are remaining weak across the Euro area. The ECB has been getting a signal: QE ≠ support for reforms. And this is bound to weigh heavily on Frankfurt.

On inflationary side, when we strip out energy prices, inflation was running at around 1.0% in November and 1.2% in October. On Services side, inflation is at 1.2% and on Food, alcohol & tobacco it is at 1.5%. This is hardly consistent with expectations for further aggressive QE deployment and were ECB to engage in more stimulus, any reversion of energy prices toward the mean will trigger much sharper tightening cycle on monetary side.

The dangers of such tightening are material. Per Bloomberg estimate, a 1% rise in the U.S. Fed rates spells estimated USD3 trillion wipe-out from the about USD45 trillion valuation in investment-grade bonds issued in major currencies, including government, corporate, mortgage and other asset-backed securities tracked by BAML index:

Source here.

European bonds are more sensitive to the ECB rate hikes than the global bonds are to the Fed hike, primarily because they are already trading at much lower yields.

Overall, thus, there is a serious risk build up in the Euro area bond markets. And this risk can go only two ways in 2016: up (and toward a much worse blowout in the future) or down (and into a serious pain in 2016). There, really, is no third way…

Monday, April 13, 2015

13/4/15: Bonds Traders: Give Us a Shake, Cause We So Sleepy...

Recently, I have been highlighting some of the problems relating to the Central Bank's driving up the valuations of government bonds across the advanced economies. In the negative-yield environment, the victims of Central Banks' activism are numerous - from banks to long-hold investors, to corporates, to capex, to savers, to... well... the fabled bonds trades(wo)men... the poor chaps (and chapettes) aren't even showing up for work nowadays: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-04-10/take-off-friday-and-monday-because-most-bond-traders-already-are because Sig. Mario is making their lives sheer misery with his euro bonds acrobatics.

Apparently, there is just not that big of a demand out there for the idea of giving money to the Governments on top of paying taxes and trading volumes are now where the rates are - in the zero corner. So the 'industry' solution is, predictably, for the Fed to raise rates. When was the last time you heard the car manufacturers begging regulators for a safety recall of their vehicles 'to jolt the complacent consumers a bit'?

Tuesday, December 30, 2014

30/12/2014: Who Owns Government Debt?

An interesting chart via DB, mapping sovereign debt holdings across the advanced economies:

As the chart clearly shows, Irish Government debt is disproportionately held in the Central Bank. Other countries with similar proportion of CB-held debt - UK, US and Japan - all deployed direct QE. Ireland, of course, deployed virtually the same QE-like stimulus predominantly to the IBRC.

Another interesting feature is the share of Government debt held by foreign agencies: roughly 20% of the total, or 11th lowest in the sample of 21 countries. That is pretty low, given the amount of PR-talk the Government has been deploying around foreign buyers of Irish bonds.

In contrast, predictably, we rank the third after Greece and Portugal in the share of Government debt held by foreign official sector. This will decline once the IMF 'repayment' is finalised. Domestic banks' holdings of Irish debt are third lowest in the sample, and domestic non-banks holdings are 5th lowest. This is unlikely to change, given the sheer quantum of Government debt outstanding, relative to the overall economy's capacity and demand, and given the low yields on Government debt being generated.

The kicker of all of this is that owing to years of mismanaged bailouts, we are now saddled with the legacy of rescuing private debt holders in the banks. This legacy is simple: instead of private debt we have official debt, held predominantly by official sectors and our own CB, guaranteed by the Irish State. In other words, more of our debt is now super-senior in both rights and default terms.

Saturday, January 18, 2014

18/1/2014: Portugal 'doin Dublin' or going for broke?

A very interesting interview with David Slanic, CEO of Tortus Capital Management LLC on Portugal's sovereign debt sustainability and the need for further debt restructuring.

http://janelanaweb.com/trends/portugal-needs-a-national-salvation-pact-with-a-short-mandate-to-restructure-the-sovereign-debt-david-salanic-tortus-capital/

Is Portugal really that close to restructuring as to pre-borrow reserves forward? Or is it pre-borrowing to do what Dublin did and exit in H2 2014 with no precautionary line of credit?..

Signals from the CDS markets? No evidence of serious markets concerns so far...

Sunday, July 14, 2013

14/7/2013: Banking Reforms : recent links

Some recent articles on Banks Reforms in the global and EU context:

"A viable alternative to Basel III prudential rules" by Stefano Micossi (9 June 2013) argues that Basel III "…proposed reforms will fail to correct flaws in the old system. The new rules are even more complicated, opaque and open to manipulation. What is needed is a radical shift to prudential rule based on a straight capital ratio."

Link: http://www.voxeu.org/article/viable-alternative-basel-iii-prudential-rules

And in a typically Bruegelesque fashion, "Basel III: Europe’s interest is to comply" by Nicolas Véron (5 March 2013) argues that since "the EU was once a champion of global financial regulatory convergence", then "the EU should drop its lacklustre inertia and pursue Basel III because, in the end, it’s in its interests to comply. EU policymakers ought to aim at enabling the adoption of a Capital Requirements Regulation that would be fully compliant with Basel III."

Link: http://www.voxeu.org/article/basel-iii-europe-s-interest-comply

His colleague, Daniel Gros is of a view that diversification is a good thing, but diversification not i regulatory space. In his "EZ banking union with a sovereign virus" (14 June 2013) he argues that: "The doom-loop between banks and the national governments played a dominant role in the Eurozone crisis for Ireland and Cyprus. A Eurozone banking union is usually viewed as the solution. This column argues that the doom-loop cannot be undone as long as banks hold oversized amounts of their government’s debt. A simple solution would be to apply the general rule that banks are prohibited from holding more than a quarter of their capital in government bonds of any single sovereign." Here's the problem, however, in both Cyprus and Ireland sovereign bonds holdings of own governments were not a problem. In Cyprus the problem was holding of Greek Government bonds, and in Ireland, the contagion mechanism was from inter-bank lending and banks' own bonds issuance to the sovereign via a blanket 2008 Guarantee.

Link: http://www.voxeu.org/article/ez-banking-union-sovereign-virus

"Implementation of Basel III in the US will bring back the regulatory arbitrage problems under Basel I" by Takeo Hoshi (23 December 2012) says that "rejigging financial regulation is in vogue. But, in the world of international finance, how well do different regulatory systems join up?" In the US context, the author "argues that the US Dodd Frank Act and Basel III are, in part, incompatible and that harmonising them may lead to unintended consequences. The US ought to tread carefully here but should also try hard to maintain the spirit of better financial regulation."

Link: http://www.voxeu.org/article/implementation-basel-iii-us-will-bring-back-regulatory-arbitrage-problems-under-basel-i

There's a huge amount of opinion published on Voxeu.org on bank regulation: http://www.voxeu.org/debates/banking-reform-do-we-know-what-has-be-done

ZeroHedge classic: http://www.zerohedge.com/node/475643 "The Secret Sauce Of Iceland's Success Story: Debt Liquidation?" argues that "That Iceland is so far the only success story in the continent of Europe, which continues sliding into an ever deeper depressionary black hole, as a result of the complete destruction of its financial sector and its subsequent rise from the ashes, is by known to most. …As it turns out, perhaps the biggest jolt to Icelandic economic growth is what we said was the correct prescription for resolving not only the US but global growth malaise that struck in 2008: debt liquidation."

Irish Times covers the outright bizarre and sublimely ironic day-dreaming that is going on in Ireland's highest policy circles. The latests instalment is transformation of the IFSC into a sort of "We've screwed up so comprehensively, we can sell this as competence" story: http://www.irishtimes.com/business/sectors/financial-services/ifsc-faces-radical-rethink-as-effects-of-crash-become-clear-1.1460832?page=2

Pearls of wisdom: "Ryan’s paper makes eight proposals, including “relaunching the IFSC brand” along product lines – global asset finance, a global servicing platform and a global listing platform." All of which have been already in place for years to various success. "The document recommends the creation of a JobsHub to allow firms seeking staff to “find people quickly and cost effectively”." Other things: setting up IFSC as a centre for 'bad banks' on foot of 'experience already present in NAMA'. This is the logic of converting Dublin Bay into a global toxic refuse dump for the UK and European waste disposal, because we 'already have considerable expertise' at the Poolbeg waste facilities. And last, but not least: converting IFSC into "global centre of excellence for property"… Even the Irish Times could not have escaped the obvious irony present in this idea.

Last, but not least, Bloomberg report on Michel Barnier balmy ideas on 'Bank-Crisis' plans for the EU: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-07-09/eu-steels-for-battle-over-bank-resolution-plans-led-by-germany.html from July 9. "The European Union’s executive arm proposed procedures for handling failing banks with a 55 billion-euro ($70 billion) backstop, setting up a showdown with Germany over control of taxpayers’ cash." Good summery of current play on this.

"A viable alternative to Basel III prudential rules" by Stefano Micossi (9 June 2013) argues that Basel III "…proposed reforms will fail to correct flaws in the old system. The new rules are even more complicated, opaque and open to manipulation. What is needed is a radical shift to prudential rule based on a straight capital ratio."

Link: http://www.voxeu.org/article/viable-alternative-basel-iii-prudential-rules

And in a typically Bruegelesque fashion, "Basel III: Europe’s interest is to comply" by Nicolas Véron (5 March 2013) argues that since "the EU was once a champion of global financial regulatory convergence", then "the EU should drop its lacklustre inertia and pursue Basel III because, in the end, it’s in its interests to comply. EU policymakers ought to aim at enabling the adoption of a Capital Requirements Regulation that would be fully compliant with Basel III."

Link: http://www.voxeu.org/article/basel-iii-europe-s-interest-comply

His colleague, Daniel Gros is of a view that diversification is a good thing, but diversification not i regulatory space. In his "EZ banking union with a sovereign virus" (14 June 2013) he argues that: "The doom-loop between banks and the national governments played a dominant role in the Eurozone crisis for Ireland and Cyprus. A Eurozone banking union is usually viewed as the solution. This column argues that the doom-loop cannot be undone as long as banks hold oversized amounts of their government’s debt. A simple solution would be to apply the general rule that banks are prohibited from holding more than a quarter of their capital in government bonds of any single sovereign." Here's the problem, however, in both Cyprus and Ireland sovereign bonds holdings of own governments were not a problem. In Cyprus the problem was holding of Greek Government bonds, and in Ireland, the contagion mechanism was from inter-bank lending and banks' own bonds issuance to the sovereign via a blanket 2008 Guarantee.

Link: http://www.voxeu.org/article/ez-banking-union-sovereign-virus

"Implementation of Basel III in the US will bring back the regulatory arbitrage problems under Basel I" by Takeo Hoshi (23 December 2012) says that "rejigging financial regulation is in vogue. But, in the world of international finance, how well do different regulatory systems join up?" In the US context, the author "argues that the US Dodd Frank Act and Basel III are, in part, incompatible and that harmonising them may lead to unintended consequences. The US ought to tread carefully here but should also try hard to maintain the spirit of better financial regulation."

Link: http://www.voxeu.org/article/implementation-basel-iii-us-will-bring-back-regulatory-arbitrage-problems-under-basel-i

There's a huge amount of opinion published on Voxeu.org on bank regulation: http://www.voxeu.org/debates/banking-reform-do-we-know-what-has-be-done

ZeroHedge classic: http://www.zerohedge.com/node/475643 "The Secret Sauce Of Iceland's Success Story: Debt Liquidation?" argues that "That Iceland is so far the only success story in the continent of Europe, which continues sliding into an ever deeper depressionary black hole, as a result of the complete destruction of its financial sector and its subsequent rise from the ashes, is by known to most. …As it turns out, perhaps the biggest jolt to Icelandic economic growth is what we said was the correct prescription for resolving not only the US but global growth malaise that struck in 2008: debt liquidation."

Irish Times covers the outright bizarre and sublimely ironic day-dreaming that is going on in Ireland's highest policy circles. The latests instalment is transformation of the IFSC into a sort of "We've screwed up so comprehensively, we can sell this as competence" story: http://www.irishtimes.com/business/sectors/financial-services/ifsc-faces-radical-rethink-as-effects-of-crash-become-clear-1.1460832?page=2

Pearls of wisdom: "Ryan’s paper makes eight proposals, including “relaunching the IFSC brand” along product lines – global asset finance, a global servicing platform and a global listing platform." All of which have been already in place for years to various success. "The document recommends the creation of a JobsHub to allow firms seeking staff to “find people quickly and cost effectively”." Other things: setting up IFSC as a centre for 'bad banks' on foot of 'experience already present in NAMA'. This is the logic of converting Dublin Bay into a global toxic refuse dump for the UK and European waste disposal, because we 'already have considerable expertise' at the Poolbeg waste facilities. And last, but not least: converting IFSC into "global centre of excellence for property"… Even the Irish Times could not have escaped the obvious irony present in this idea.

Last, but not least, Bloomberg report on Michel Barnier balmy ideas on 'Bank-Crisis' plans for the EU: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-07-09/eu-steels-for-battle-over-bank-resolution-plans-led-by-germany.html from July 9. "The European Union’s executive arm proposed procedures for handling failing banks with a 55 billion-euro ($70 billion) backstop, setting up a showdown with Germany over control of taxpayers’ cash." Good summery of current play on this.

Thursday, May 30, 2013

30/5/2013: Future Interest Rates & the 'Impossible Monetary Policy Dilemma'

Recently, I wrote about the monetary policy exit dilemma (here) on foot of IMF research. This week, BIS published another paper on the issue of long-term interest rates problem presented by the need to eventually unwind the extraordinary monetary policy measures (including this). Do note that the dilemma also covers the problem of unwinding banking sector leverage overhang (see presentation covering, among other things, this matter here).

BIS paper is linked here.

We might want to believe in the permanence of the low (negative currently) long term rates, but, alas, that is not so. I have written about this on a number of occasions, including in my Sunday Times columns. But a reminder from BIS:

Or even at policy rates level (here), or per BIS:

I don't know about you, but any reversion to the mean will end the bond bubble like the property bust ended the REITs bubble - solidly and overnight. And when the IMF said 6% swing up on yields, they weren't kidding:

Ditto for term premium uplift on reversion:

So unless you are into 'This Time It'll Be Different, For Sure' argument, then brace yourselves for the ride - it is coming. May be not in 2013-2014, but one day it is...

The quality risk-free paper mountain has grown... just as all the ABS and RMBS and other BS... and we know even absent excel errors from R&R 2010 how that stuff ended...

BIS paper is linked here.

We might want to believe in the permanence of the low (negative currently) long term rates, but, alas, that is not so. I have written about this on a number of occasions, including in my Sunday Times columns. But a reminder from BIS:

Or even at policy rates level (here), or per BIS:

I don't know about you, but any reversion to the mean will end the bond bubble like the property bust ended the REITs bubble - solidly and overnight. And when the IMF said 6% swing up on yields, they weren't kidding:

So unless you are into 'This Time It'll Be Different, For Sure' argument, then brace yourselves for the ride - it is coming. May be not in 2013-2014, but one day it is...

The quality risk-free paper mountain has grown... just as all the ABS and RMBS and other BS... and we know even absent excel errors from R&R 2010 how that stuff ended...

Thursday, May 16, 2013

16/5/2013: On That Impossible Monetary Policy Dilemma

At last, the IMF has published something beefy on the extraordinary (or so-called 'unconventional') monetary policy instruments unrolled by the ECB, BOJ, BOE and the Fed since the start of the crisis in the context of the question I been asking for some time now: What happens when these measures are unwound?

See http://liswires.com/archives/2102 and http://trueeconomics.blogspot.ie/2012/10/28102012-ecb-and-technocratic-decay.html

The papers: UNCONVENTIONAL MONETARY POLICIES—RECENT EXPERIENCE AND PROSPECTS and UNCONVENTIONAL MONETARY POLICIES—RECENT EXPERIENCE AND PROSPECTS—BACKGROUND PAPER should be available on the IMF website shortly.

Box 2 in the main paper is worth a special consideration as it covers Potential Costs of Exit to Central Banks. Italics are mine.

Per IMF: "Losses to central bank balance sheets upon exit are likely to stem from a maturity mismatch between assets and liabilities. In normal circumstances, higher interest rates—and thus lower bond prices—would lead to an immediate valuation loss to the central bank. These losses, though, would be fully recouped if assets were held to maturity. [In other words, normally, when CBs exit QE operations, they sell the Government bonds accumulated during the QE. This leads to a rise in supply of Government bonds in the market, raising yields and lowering prices of these bonds, with CBs taking a 'loss' on lower prices basis. In normal cases, CBs tend to accumulate shorter-term Government bonds in greater numbers, so sales and thus price decreases would normally be associated with the front end of maturity profile - meaning with shorter-dated bonds. Lastly, in normal cases of QE, some of the shorter-dated bonds would have matured by the time the CBs begin dumping them in the market, naturally reducing some of the supply glut on exits.]

But current times are not normal. "Two things have changed with the current policy environment: (i) balance sheets have grown enormously, and (ii) assets purchased are much longer-dated on average and will likely not roll-off central bank balance sheets before exit begins."

This means that in current environment, as contrasted by normal unwinding of the QE operations. "…valuation losses will be amplified and become realized losses if central banks sell assets in an attempt to permanently diminish excess reserves. But central banks will not be able to shrink their balance sheets overnight. In the interim, similar losses would arise from paying higher interest rates on reserves (and other liquidity absorbing instruments) than earning on assets held (mostly fixed coupon payments). This would not have been the case in normal times, when there was no need to sell significant amounts of longer-dated bonds and when most central bank liabilities were non-interest bearing (currency in circulation)."

The IMF notes that "the ECB is less exposed to losses from higher interest rates as its assets— primarily loans to banks rather than bond purchases—are of relatively short maturity and yields of its loans to banks are indexed on the policy rate; the ECB is thus not included in the estimates of losses that follow." [Note: this does not mean that the ECB unwinding of extraordinary measures will be painless, but that the current IMF paper is not covering these. In many ways, ECB will face an even bigger problem: withdrawing liquidity supply to the banks that are sick (if not permanently, at least for a long period of time) will risk destabilising the financial system. This cost to ECB will likely be compounded by the fact that unwinding loans to banks will require banks to claw liquidity out of the existent assets in the environment where there is already a drastic shortage of credit supply to the real economy. Lastly, the ECB will also face indirect costs of unwinding its measures that will work through the mechanism similar to the above because European banks used much of ECB's emergency liquidity supply to buy Government bonds. Thus unlike say the BOE, ECB unwinding will lead to banks, not the ECB, selling some of the Government bonds and this will have an adverse impact on the Sovereign yields, despite the fact that the IMF does not estimate such effect in the present paper.]

The chart below "shows the net present value (NPV) estimate of losses in three different scenarios." Here's how to read that chart:

- "Losses are estimated given today’s balance sheet (no expansion) and the balance sheet that would result from expected purchases to end 2013 (end 2014 for the BOJ, accounting for QQME).

- "Losses are estimated while assuming everything else remains unchanged (notably absent capital gains or income from asset holdings)… [so that] no stance is taken as to the precise path and timing of exit. ...These losses—which may be significant even if spread over several years—would impact fiscal balances through reduced profit transfers to government.

- "Scenario 1 foresees a limited parallel shift in the yield curve by 100 bps from today’s levels.

- "Scenario 2, a more likely case corresponding to a stronger growth scenario requiring a steady normalization of rates, suggests a flatter yield curve, 400 bps higher at the short end and 225 bps at the long. The scenario is similar to the Fed’s tightening from November 1993 to February 1995, which saw one year rates increase by around 400bps. Losses in this case would amount to between 2 percent and 4.3 percent of GDP, depending on the central bank.

- "Scenario 3 is a tail risk scenario, in which policy has to react to a loss of confidence in the currency or in the central bank’s commitment to price stability, or to a severe commodity price shock with second round effects. The short and long ends of the yield curve increase by 600 bps and 375 bps respectively, and losses rise to between 2 percent and 7.5 percent of GDP.

- "Scenarios 2 and 3 foresee somewhat smaller hikes for the BOJ, given the persistence of the ZLB.

And now on transmission of the shocks: "The appropriate sequence of policy actions in an eventual exit is relatively clear.

- "A tightening cycle would begin with some forward guidance provided by the central bank on the timing and pace of interest rate hikes. [At which point bond markets will also start repricing forward Government paper, leading to bond markets prices drops and mounting paper losses on the assets side of CBs balance sheets]

- "It would then be followed by higher short-term interest rates, guided over a first (likely lengthy) period by central bank floor rates (which can be hiked at any time, independently of the level of reserves) until excess reserves are substantially removed. [So shorter rates will rise first, implying that shorter-term interbank funding costs will also rise, leading to a rise in lone rates disproportionately for banks reliant on short interbank loans - guess where will Irish banks be by then if the 'reforms' we have for them in mind succeed?]

- "Term open market operations (“reverse repos” or other liquidity absorbing instruments) would be used to drain excess reserves initially; outright asset sales would likely be more difficult in the early part of the transition, until the price of longer-term assets had adjusted. Higher reserve requirements (remunerated or unremunerated) could also be employed." [All of which mean that whatever credit supply to private sector would have been before the unwinding starts, it will become even more constrained and costlier to obtain once the unwinding begins.]

- For a kicker to that last comment: "The transmission of policy, though, is likely to somewhat bumpy in the tightening cycle associated with exit. Reduced competition for funding in the presence of substantial excess reserve balances tends to weaken the transmission mechanism. Though higher rates paid on reserves and other liquidity absorbing instruments should generally increase other short-term market rates (for example, unsecured interbank rates, repo rates, commercial paper rates), there may be some slippage, with market rates lagging. This could occur because of market segmentation, with cash rich lenders not able to benefit from the central bank’s official deposit rate, or lack of arbitrage in a hardly operating money market flush with liquidity. Also, there may be limits as to how much liquidity the central bank can absorb at reasonable rates, since banks would face capital charges and leverage ratio constraints against repo lending." [But none of these effects - generally acting to reduce immediate pressure of CB unwinding of QE measures - apply to the Irish banks and will unlikely apply to the ECB case in general precisely because the banks own balance sheets will be directly impacted by the ECB unwinding.]

- "There is also a risk that even if policy rates are raised gradually, longer-term yields could increase sharply. While central banks should be able to manage expectations of the pace of bond sales and rise in future short-term rates—at least for the coming 2 to 3 years—through enhanced forward guidance and more solid communication channels, they have less control over the term premium component of long-term rates (the return required to bear interest rate risk) and over longer-term expectations. These could jump because leveraged investors could “run for the door” in the hope of locking in profits, because of expected reverse portfolio rebalancing effects from bond sales, uncertainty over inflation prospects or because of fiscal policy, financial stability or other macro risks emerging at the time of exit. To the extent a rise in long-term rates triggers cross-border flows, exchange rate volatility is bound to increase, further complicating policy decisions." [All of which means two things: (a) any and all institutions holding 'sticky' (e.g. mandated) positions in G7 bonds will be hammered by speculative and book-profit exits (guess what these institutions are? right: pension funds and insurance companies and banks who 'hold to maturity' G7-linked risky bonds - e.g peripheral euro area bonds), and (b) long-term interest rates will rise and can rise in a 'jump fashion' - abruptly and significantly (and guess what determines the cost of mortgages and existent not-fixed rate loans?).]

And so we do it forget the ECB plight, here's what the technical note had to say about Frankfurt's dilemma: "The ECB faces relatively little direct interest rate risk, as the bulk of its loan assets are linked to its short-term policy rate. However, it may be difficult for the ECB to shrink its balance sheet, as those commercial banks currently borrowing from the ECB may not easily be able to repay loans on maturity. The ECB could use other instruments to drain surplus liquidity, but could then face some loss of net income as the yield on liquidity-draining open market operations (OMOs) could exceed the rate earned on lending, assuming a positively-sloped yield curve, if draining operations were of a longer maturity." [I would evoke the 'No Sh*t, Sherlock" clause here: who could have thought Euro area's commercial banks "may not easily be able to repay loans on maturity". I mean they are beaming with health and are full of good loans they can call in to cover an ECB unwind call… right?]

Obviously, not the IMF as it does cover the 'geographic' divergence in unwinding risks: "But the ECB potentially faces credit risk on its lending to the banking system for financial stability purposes. In a “benign” scenario, where monetary tightening is a response to higher inflation resulting from economic growth, non-performing loans should fall and bank balance sheets should improve. But even then, some areas of the eurozone may lag in economic recovery. Banks in such areas could come under further pressure in a rising rate environment: weak banks may not be able to pass on to weak customers the rising costs of financing their balance sheets." [No prize for guessing which 'areas' the IMF has in mind for being whacked the hardest with ECB unwinding measures.]

So would you like to take the centre-case scenario at 1/2 Fed impact measure for ECB costs and apply to Ireland's case? Ok - we are guessing here, but it will be close to:

- Euro area-wide impact of -1.0-1.5% GDP shaved off with most impact absorbed by the peripheral states; and

- Yields rises of ca 200-220bps on longer term paper, which will automatically translate into massive losses on banks balancesheets (and all balancesheets for institutions holding Government bonds).

- The impact of (2) will be more severe for peripheral countries via 2 channels: normal premium channel on peripheral bonds compared to Bunds and via margins hikes on loans by the banks to compensate for losses sustained on bonds.

- Net result? Try mortgages rates rising over time by, say 300bps? or 350bps? You say 'extreme'? Not really - per crisis historical ECB repo rate averages at 3.10% which is 260bps higher than current repo rate...

Ooopsy... as some would say. Have a nice day paying that 30 year mortgage on negative equity home in Co Meath (or Dublin 4 for that matter).

Friday, May 3, 2013

3/5/2013: Basel 2.5 can lead to increased liquidity & contagion risks

Banca d'Italia research paper No. 159, "Basel 2.5: potential benefits and unintended consequences" (April 2013) by Giovanni Pepe looks at the Basel III framework from the risk-weighting perspective. Under previous Basel rules, since 1996, "…the Basel risk-weighting regime has been based on the distinction between the trading and the

banking book. For a long time credit items have been weighted less strictly if held in the trading book, on the assumption that they are easy to hedge or sell."

Alas, the assumption of lower liquidity risks associated with assets held on trading book proved to be rather faulty. "The Great Financial Crisis made evident that banks declared a trading intent on positions that proved difficult or impossible to sell quickly. The Basel 2.5 package was developed in 2009 to better align trading and banking books’ capital treatments." Yet, the question remains as to whether the Basel 2.5 response is adequate to properly realign risk pricing for liquidity risk, relating to assets held on trading book.

"Working on a number of hypothetical portfolios [the study shows] that the new rules fell short of reaching their target and instead merely reversed the incentives. A model bank can now achieve a material capital saving by allocating its credit securities to the banking book [as opposed to the trading book], irrespective of its real intention or capability of holding them until maturity. The advantage of doing so is particularly pronounced when the incremental investment increases the concentration profile of the trading book, as usually happens for exposures towards banks’ home government. Moreover, in these cases trading book requirements are exposed to powerful cliff-edge

effects triggered by rating changes."

In the nutshell, Basel 2.5 fails to get the poor quality assets risks properly priced and instead created incentives for the banks to shift such assets to the different section of the balance sheet. The impact of this is to superficially inflate values of sovereign debt (by reducing risk-weighted capital requirements on these assets). Added effect of this is that Basel 2.5 inadvertently increases the risk of sovereign-bank-sovereign contagion cycle.

The paper is available at: http://www.bancaditalia.it/pubblicazioni/econo/quest_ecofin_2/qef159/QEF_159.pdf

Thursday, February 28, 2013

28/2/2013: Risk-free assets getting thin on the ground

Neat summary of the problem with the 'risk-free' asset class via ECR:

Excluding Germany and the US - both with Negative or Stable/Negative outlook, there isn't much of liquid AAA-rated bonds out there... And Canada and Australia are the only somewhat liquid issuers with Stable AAA ratings (for now). Which, of course, means we are in a zero-beta CAPM territory, implying indeterminate market equilibrium and strong propensity to shift market portfolio on foot of behavioural triggers... ouchy...

Friday, February 17, 2012

17/2/2012: ECB Swap Creates a New Structure of Seniority

This week marked a significant point of change in the very fabric of the fixed income markets. On Friday, the ECB announced that it has completed the swap on the old Greek bonds it held on its books for new bond.

The ECB swap in effect exchanged old Greek bonds for bonds of identical structure and nominal value, implying that the ECB has received the full face value of the bonds it has purchased in the markets at the discount on the face value. The ECB will also not forego the coupon payments due on the bonds, implying that over time, ECB will book profit from its purchases of Greek bonds. It is worth noting that this is based on the reports in the media, citing various official sources. The ECB has no inclination of clarifying any details of the transaction.

The ECB also precluded National Central Banks (some of which do hold Greek bonds) from participating in the swap. However, the ECB has signaled that it might (again, no commitment or compulsion) distribute the profits earned from the Greek bonds purchases to the national central banks of the countries contributing to the bailout.

Currently, the ECB holds some €219.5 billion worth of sovereign bonds (primarily those of PIIGS states) that it has began accumulating since May 2010.

The greatest significance of today's swap is not, however, in the fact that the ECB is likely to make a tidy profit from its operations designed to help Greece. No, the real significance is that in one step, the ECB has completely re-shaped the seniority structure of sovereign bonds issued by all of the euro area governments.

Before the swap, the seniority of bonds was established under the bonds terms and conditions alone, implying equal treatment of all bondholders, with any variation in sovereign bonds security arising from any potential (and highly costly and uncertain) court actions by investors against the sovereigns. Now, the structure has ECB as the holder of the Super Senior bonds with ECB seniority imposed over and above all other bondholders.

In addition, by not bringing into the swap National Central Banks, the ECB threw open the possibility of another sub-tier of seniority emerging over time. In the case of imposition of Collective Action Clauses by Greece or any other sovereign, such clauses will automatically imply non-zero probability of a loss on bonds held by the NCBs. Arguably, they too might follow the ECB line and demand, collectively or separately (as Germany, the Netherlands and Finland are currently already doing) that their holdings of bonds should also be exempt from such a clause. This means that ECB swap opens up a possibility of a new tier of security forming - the tier subordinated to Super-Senior ECB holdings. This can take a form of a Senior tier or Senior Secured tier (if collateral or other security arrangements are put in place, e.g. some sort of an escrow account etc).

The unknown at this stage is the issue of seniority of non-euro area sovereigns holding euro area government bonds. In particular - will China and Japan, the US and Australia etc demand some sort of Senior or even Super-Senior seniority now that the ECB has elevated itself to the level of IMF?

This means that any private investor in Government bonds (note, these are themselves senior to special Government-issued bonds, such as postal certificates, domestic savings bonds etc) is now left a holder of the Junior or Subordinated bonds, despite the fact that on the 'box' the bonds are identical to those held by the ECB, NCBs, Foreign Governments, etc.

The entire market for euro area bonds is now wholly mispriced when risk-return relationships are concerned. Just like that, in a blink of an eye, the European system destroyed legal and financial order and undermined private property rights.

Note: The above arguments are taken from the simple investment risk perspective. Legal perspective is yet to be defined and I welcome any comments on this and/or links to it.

The ECB swap in effect exchanged old Greek bonds for bonds of identical structure and nominal value, implying that the ECB has received the full face value of the bonds it has purchased in the markets at the discount on the face value. The ECB will also not forego the coupon payments due on the bonds, implying that over time, ECB will book profit from its purchases of Greek bonds. It is worth noting that this is based on the reports in the media, citing various official sources. The ECB has no inclination of clarifying any details of the transaction.

The ECB also precluded National Central Banks (some of which do hold Greek bonds) from participating in the swap. However, the ECB has signaled that it might (again, no commitment or compulsion) distribute the profits earned from the Greek bonds purchases to the national central banks of the countries contributing to the bailout.

Currently, the ECB holds some €219.5 billion worth of sovereign bonds (primarily those of PIIGS states) that it has began accumulating since May 2010.

The greatest significance of today's swap is not, however, in the fact that the ECB is likely to make a tidy profit from its operations designed to help Greece. No, the real significance is that in one step, the ECB has completely re-shaped the seniority structure of sovereign bonds issued by all of the euro area governments.

Before the swap, the seniority of bonds was established under the bonds terms and conditions alone, implying equal treatment of all bondholders, with any variation in sovereign bonds security arising from any potential (and highly costly and uncertain) court actions by investors against the sovereigns. Now, the structure has ECB as the holder of the Super Senior bonds with ECB seniority imposed over and above all other bondholders.

In addition, by not bringing into the swap National Central Banks, the ECB threw open the possibility of another sub-tier of seniority emerging over time. In the case of imposition of Collective Action Clauses by Greece or any other sovereign, such clauses will automatically imply non-zero probability of a loss on bonds held by the NCBs. Arguably, they too might follow the ECB line and demand, collectively or separately (as Germany, the Netherlands and Finland are currently already doing) that their holdings of bonds should also be exempt from such a clause. This means that ECB swap opens up a possibility of a new tier of security forming - the tier subordinated to Super-Senior ECB holdings. This can take a form of a Senior tier or Senior Secured tier (if collateral or other security arrangements are put in place, e.g. some sort of an escrow account etc).

The unknown at this stage is the issue of seniority of non-euro area sovereigns holding euro area government bonds. In particular - will China and Japan, the US and Australia etc demand some sort of Senior or even Super-Senior seniority now that the ECB has elevated itself to the level of IMF?

This means that any private investor in Government bonds (note, these are themselves senior to special Government-issued bonds, such as postal certificates, domestic savings bonds etc) is now left a holder of the Junior or Subordinated bonds, despite the fact that on the 'box' the bonds are identical to those held by the ECB, NCBs, Foreign Governments, etc.

The entire market for euro area bonds is now wholly mispriced when risk-return relationships are concerned. Just like that, in a blink of an eye, the European system destroyed legal and financial order and undermined private property rights.

Note: The above arguments are taken from the simple investment risk perspective. Legal perspective is yet to be defined and I welcome any comments on this and/or links to it.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)