An interesting paper, THE DETERMINANTS OF NATIONAL COMPETITIVENESS by Mercedes Delgado, Christian Ketels, Michael E. Porter and Scott Stern (NBER Working Paper 18249) looked at three broad and interrelated drivers of foundational competitiveness:

- social infrastructure and political institutions (SIPI),

- monetary and fiscal policy (MFP), and

- the microeconomic environment.

The study defined foundational competitiveness as "the expected level of output per working-age individual that is supported by the overall quality of a country as a place to do business". The paper focused on output per potential worker, which is "a broader measure of national productivity than output per current worker". This "reflects the dual role of workforce participation and output per worker in determining a nation’s standard of living".

Using data "covering more than 130 countries over the 2001-2008 period", the authors found "a positive and separate influence of each driver on output per potential worker". Specifically, "we find significant evidence for the positive and separate influence of SIPI, MFP, and the microeconomic conditions on national competitiveness":

- Consistent with prior studies, institutions (SIPI) positively influence national output per potential worker;

- However, microeconomic conditions have a strong positive impact as well, even after controlling for current institutional conditions;

- Microeconomic conditions have a positive influence on competitiveness even after controlling for historical institutional conditions and incorporating country fixed effects (which offer a broader measure of a country’s unobserved legacy);

- Current institutions and macroeconomic policies "seem largely endogenous to historical legacies";

- "Overall, the findings strongly suggest that contemporaneous public and private choices, especially those that relate to microeconomic competitiveness, are an important driver of country output per potential worker and, ultimately, prosperity".

The paper also defined a new concept, global investment attractiveness, "which is the cost of factor inputs relative to a country’s competitiveness".

Using the new metric, the authors rank the countries with respect to their global investment competitiveness:

The unpleasant bit is that in 2010, a year after we began the process of 'competitiveness improvements' that has stalled since around mid 2011, we were ranked just 24th. The pleasant bit... we still made it into top 25.

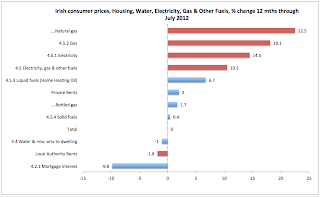

And in terms of other comparatives, here are few charts:

Oh, the naughty, naughty authors did get some things right: "In the case of Ireland, we used GNP instead of GDP because of the size of dividend outflows to foreign investors".

And here's what they had to say in terms of their analysis of the Global Investment Attractiveness scores (GIA): "Countries with high GIA tend to experience a strong positive growth, including China and India (with growth rates above 8% and 4%, respectively). In contrast, countries with low GIA tend to experience a high contraction in output with growth rates below the median value, including Italy, Spain, Ireland, and Venezuela, among others."

Now, wait, is that really the neighborhood we (Ireland) are in? You wouldn't think so from our policymakers/IDA/EI/Forfas/ESRI/CBofI/... statements.