An interesting article from the BIS on the impact of deflation risks on growth and post-crises recovery. Authored by Borio, Claudio E. V. and Erdem, Magdalena and Filardo, Andrew J. and Hofmann, Boris, and titled "The Costs of Deflations: A Historical Perspective" (BIS Quarterly Review March 2015: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2580289), the paper looks at the common concern amongst the policymakers that falling prices of goods and services are very costly in terms of economic growth.

The authors "test the historical link between output growth and deflation in a sample covering 140 years for up to 38 economies. The evidence suggests that this link is weak and derives largely from the Great Depression. But we find a stronger link between output growth and asset price deflations, particularly during postwar property price deflations. We fail to uncover evidence that high debt has so far raised the cost of goods and services price deflations, in so-called debt deflations. The most damaging interaction appears to be between property price deflations and private debt."

But there is much more than this to the paper. So some more colour on the above.

"Concerns about deflation [are] …shaped by the deep-seated view that deflation, regardless of context, is an economic pathology that stands in the way of any sustainable and strong expansion."

Do note that I have been challenging this thesis for some time now, precisely on the grounds of: 1) causality (deflation being caused by weak growth, not the other way around) and 2) link between corporate and household debt and deflation via monetary policy / interest rates channel.

Per authors, "The almost reflexive association of deflation with economic weakness is easily explained. It is rooted in the view that deflation signals an aggregate demand shortfall, which simultaneously pushes down prices, incomes and output. But deflation may also result from increased supply. Examples include improvements in productivity, greater competition in the goods market, or cheaper and more abundant inputs, such as labour or intermediate goods like oil. Supply-driven deflations depress prices while raising incomes and output."

Besides the supply side argument, there is more: "…even if deflation is seen as a cause, rather than a symptom, of economic conditions, its effects are not obvious. On the one hand, deflation can indeed reduce output. Rigid nominal wages may aggravate unemployment. Falling prices raise the real value of debt, undermining borrowers’ balance sheets, both public and private – a prominent concern at present given historically high debt levels. Consumers might delay spending, in anticipation of lower prices. And if interest rates hit the zero lower bound, monetary policy will struggle to encourage spending. On the other hand, deflation may actually boost output. Lower prices increase real incomes and wealth. And they may also make export goods more competitive."

Note: the authors completely ignore the interest cost channel for debt.

Meanwhile, "…while the impact of goods and services price deflations is ambiguous a priori, that of asset price deflations is not. As is widely recognised, asset price deflations erode wealth and collateral values and so undercut demand and output. Yet the strength of that effect is an empirical matter. One problem in assessing the cost of goods and services price deflations is that they often coincide with asset price deflations. It is possible, therefore, to mistakenly attribute to the former the costs induced by the latter."

The BIS paper analysis is "based on a newly constructed data set that spans more than 140 years, from 1870 to 2013, and covers up to 38 economies. In particular, the data include information on both equity and property prices as well as on debt."

The study reaches three broad conclusions:

- "First, before accounting for the behaviour of asset prices, we find only a weak association between goods and services price deflations and growth; the Great Depression is the main exception."

- "Second, the link with asset price deflations is stronger and, once these are taken into account, it further weakens the association between goods and services price deflations and growth."

- "Finally, we find some evidence that high private debt levels have amplified the impact of property price deflations but we detect no similar link with goods and services price deflations." Note: this means that the ECB-targeted deflation (goods and services deflation) is a completely wrong target to aim for in the presence of private debt overhang. Just as I have been arguing for ages now.

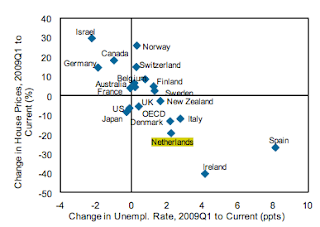

Let's give some more focus to the paper findings on debt-deflation links: "Against the background of record high levels of both public and private debt (Graph 7 below), a key concern about the output costs of goods and services price deflation in the current debate is “debt deflation”, ie the interaction of deflation with debt."

Yep, you got it - the entire monetary policy today is based on the ideas tracing back to the 1930s and anchored in the experience that is only partially replicated today. In effect, we are fighting a new disease with false ancient prescriptions for an entirely different disease.

To assess the link between debt and deflation effects on growth, the authors take two measures into account:

- "One is simply its corresponding debt ratio to GDP."

- "The other is a measure of “excess debt”, which should, in principle, be more relevant. We use the deviation of credit from its long-term trend, or the “credit gap” – a variable that in previous work has proved quite useful in signalling future financial distress."

Per authors, "The results point to little evidence in support of the debt deflation hypothesis, and suggest a more damaging interaction of debt with asset prices, especially property prices. Focusing on the cumulative growth performance over five year horizons for simplicity, there is no case where the interaction between the goods and services price peaks and debt is significantly negative. By contrast, we find signs that debt makes property price deflations more costly, at least when interacted with the credit gap measure."

So deflation in asset prices (property bust) is bad when household debt is high. Why?

Per study: "…these results suggest that high debt or a period of excessive debt growth has so far not increased in a visible way the costs of goods and services price deflations. Instead, it seems to have added to the strains that property price deflations in particular impose on balance sheets. …Why could the interaction of debt with asset prices matter and that with goods and services prices not matter, or at least less so? A possible explanation has to do with the size and nature of the corresponding wealth effects. For realistic scenarios, the size of the net wealth losses from asset price deflations can be much larger. Consider, for instance, the 2008 crisis in the United States,... the corresponding losses amounted to roughly $9.1 trillion and $11.3 trillion, respectively. By contrast, a hypothetical deflation of, say, 1% per year over three years would imply an increase in the real value of public and private debt of roughly $1.1 trillion (about $0.4 trillion for households and roughly $0.35 trillion each for the non-financial corporate and public sector). Moreover, the nature of the losses is quite different in the two cases. Asset price deflations represent declines in (at least perceived) aggregate net wealth; by contrast, declines in goods and services prices are mainly re-distributional. For instance, in the case of the public sector, the higher debt burden reflects the increase in the real purchasing power of debt holders."

And herein rests a major omission in the study: following asset (property) busts, accommodative monetary policy leads to a reduced cost of debt servicing for households that suffer simultaneous collapse in their nominal incomes and in their net wealth. This accommodation is deflating the cost of debt being carried. If it is accompanied by goods and services price deflation, such deflation is also boosting purchasing power of reduced nominal incomes. In simple terms, there is virtuous cycle emerging: debt servicing deflation reinforces real incomes support from goods and services deflation.

Now, reverse the two: raise rates and simultaneously hike consumer prices. what do you get?

- Debt servicing costs rise, disposable income left for consumption and investment falls;

- Inflation in goods and services reduces purchasing power of the already diminished income.

Any idea how this scenario (being pursued by the likes of the ECB) going to help the economy? I have none.