Very interesting research on tax progressivity using Swedish data:

Bengtsson, Niklas, Holmlund, Bertil and Waldenström, Daniel paper "Lifetime Versus Annual Tax Progressivity: Sweden, 1968-2009" (June 29, 2012, CESifo Working Paper Series No. 3856: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2098702) looked at the evolution of tax progressivity in Sweden from both annual and lifetime perspectives.

Per authors, "a fundamental problem with conventional assessments of tax burdens is that they typically rely on annual cross-sectional outcomes. Incomes vary over the life cycle, with young people often being low-income earners regardless of whether they will be high-paid surgeons or low- paid clerks in the future. Old-age pensioners typically do not pay payroll taxes, even though they may well earn more than younger individuals in the labor force. Capital gains are typically observable and taxed when they are realized rather than when they accrue, and such one- shot realizations may not accurately depict the lifetime income status or lifetime tax burden. Accounting for lifetime variations in both income and the ability to pay taxes is important for making a balanced assessment of the trade-off between the equity and efficiency of the tax system."

The paper looks at the implications of studying tax progressivity in an annual versus a lifetime perspective by exploiting a "rich data source with register information on the taxes paid and benefits received by a large and nationally representative sample of individuals".

The authors use a panel covering a 42-year period "to compute measures of “life- time tax progressivity”, relating information about actual lifetime tax payments and actual lifetime incomes for various parts of the distribution of lifetime incomes… The richness and size of our data – a sample size of approximately 200,000 individuals per year – allow us to compare narrow in- come segments at the top of the income distribution, such as percentiles and tenths of percentiles. Such focus is of particular relevance when pinpointing the differing impacts of labor and capital taxation."

Another major contribution of the study is "providing a comprehensive assessment of how the redistributive properties of the Swedish tax system have evolved in recent decades. The Swedish tax system has undergone major changes over the past 40 years. The overall tax burden has increased, and government tax revenues have gradually become more dependent on social security contributions and value-added taxes. Some specific reforms are particularly noteworthy. In 1971, the traditional system with joint taxation of married couples was replaced by a system in which each spouse pays taxes on his or her own income. The tax reform of 1991, called the “tax reform of the century” for its groundbreaking impact, involved substantial cuts in marginal income taxes along with the introduction of a dual income tax system in which earned income and capital income are taxed at different rates. More recent reforms include the abolition of the wealth tax as well as the introduction of a system with earned income tax credits."

Core results are:

First, the study finds that "lifetime tax progressivity is lower than tax progressivity in almost any single year. This finding is primarily due to the considerable within-life redistribution, where, e.g., the amounts received as student or old- age support almost offset the taxes as income earner."

Second, the authors "show that the discrepancy between annual and lifetime tax progressivity reflects the transitory nature of low-income status rather than the transitory nature of high income. Many of the individuals earning low or zero market income thus do not permanently belong to the bottom of the income distribution; they can be workers who are temporarily outside the labor market, unemployed, in educational programs or on sick leave. These individuals appear to be greatly “favored” by the tax-cum-benefit system when using annual data as opposed to lifetime estimates. By contrast, transitory high-income shocks, such as those caused by large realized capital gains, fall mainly on those who have already high permanent incomes. At the top of the income distribution, annual progressivity estimates therefore correlate highly with lifetime tax burdens."

Third, the authors "document the evolution of Swedish tax progressivity and find that it has followed an inverted U-shape over the past four decades, increasing sharply in the 1970s and dropping in the 1990s and 2000s. …When only actual taxes are considered, the primary source of the variation in progressivity appears to be changes in the tax system, in particular the tax reforms of 1971 and 1991, rather than trends in the distribution of market incomes. The dramatic rise in unemployment – and thus associated transfers – during the economic crisis of the 1990s increased the degree of tax-and-transfer progressively."

Moreover, "comparing Sweden’s experience with progressivity with that of Great Britain and the U.S., taxes in Sweden appear less progressive, primarily due to the high levels of income and payroll taxes paid by low-income earners."

Lastly, the study "decomposition of tax bases, in which we include not only different income taxes but also pay- roll, wealth and consumption taxes, reveals drastic restructuring over the study period. In particular, payroll taxes have become increasingly important, whereas capital taxation (including taxes on capital income, real estate, and wealth) has diminished substantially."

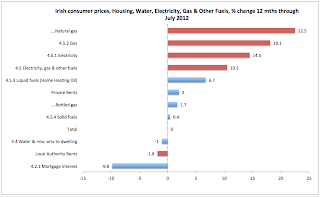

A neat summary in charts: