My Sunday Times article from April 29, 2012 (unedited version).

When first published, the Fiscal Compact (formally known as

the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and

Monetary Union) was billed as a ground-breaking exercise in European

legislative activism. The main innovation of the treaty was not its content

(which largely regurgitates already existent fiscal constraints established

under the Maastricht Treaty), but its compact size and

designed-to-be-digestible language.

Few months down the road, and the Fiscal Compact has become

a subject to numerous conflicting claims and interpretations, thanks to both

side of the referendum debate in Ireland. Mythology that surrounds the Fiscal

Compact is impressively wide and growing. The fog of politicised sloganeering

and scaremongering on the ‘Yes’ side is well matched by the clouds of emotive

and quasi-economic nonsense from the ‘No’ camp.

The main alleged problem with the Compact is that its core

rules – the 60% debt/GDP limit for Government borrowings, the 1/20 adjustment

rule for dealing with excess public debt, the 3% deficit ceiling and the 0.5%

structural deficit break – amount to prohibiting of the Keynesian economic

policies in the future. This argument is commonly advanced by the Fiscal

Compact opponents and implies that in the future crises, Ireland will not be

able to use stimulative Government spending to support its economy.

In practice, however, Fiscal Compact restricts, but not

eliminates the room for deficit financing. In the current economic conditions,

under full compliance with the deficit rules, Irish Government would have been

able to run a deficit of at least 2.97% of GDP – much lower than 8.6% targeted

under Budget 2012, but close to 3.2% deficit forecast for 2012 for the euro

area.

Far from ‘killing Keynesianism’, the Fiscal Compact induces

in the longer run fiscal policies that are consistent with Keynesian economics.

Any state that wants to secure a ‘fiscal stimulus’ cushion for future crises should

accumulate surplus resources during the times of economic expansions, not rely

on the goodwill of the bond markets to supply debt financing to the Governments

when their economies begin to tank.

The treaty does limit significantly the state capacity to

accumulate debt in the future. In the long run, debt to GDP ratio should

converge to the ratio of average deficits to the long-term growth potential.

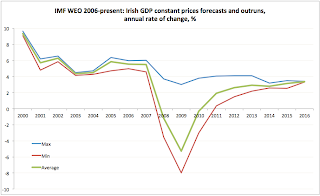

Based on IMF projections, our structural deficit for 2014-2017 will average over

2.7% of GDP, which implies Fiscal Pact-consistent government deficits around

1.6-1.7% of GDP. Assuming long-term nominal growth of 4-4.5% per annum, our

‘sustainable’ level of debt should be around 36-40% of GDP. Although no one

expects (or requires) Ireland to draw down our public debt to these levels any

time soon, over decades, this is the level we will be heading toward if we are

to comply with the Fiscal Compact rules.

On the ‘Yes’ side, the biggest myth concerning the Fiscal

Compact is that adopting the treaty will ensure that no more fiscal crises the

likes of which we have experienced since 2008 will befall this state.

In reality, the collapse of exchequer finances in Ireland

has been driven by a number of factors, completely outside the matters covered

by the Fiscal Compact.

Firstly, significant proportion of our 2008-2011 deficits

arises from the state response to the banking sector implosion and closely

correlated property sector collapse. The latter was also a primary driver for

the decline in tax revenues. The former was a policy choice. Thirdly, our

deficits were driven not just by the fiscal performance itself, but also by the

unsustainable nature of our government spending and taxation policies. For

example, during the boom, Irish Governments consistently acted to increase

automatic payments relating to unemployment and social welfare financed on the

back of tax revenues windfall from property transactions. Property revenues

collapse coincident with increases in unemployment has led to an explosion of

unfunded state liabilities.

None of these shocks could have been offset or compensated

for by the Fiscal Compact-mandated measures. In fact, during the 2000-2007

period, Irish Governments’ fiscal stance, on the surface, was well ahead of the

Fiscal Compact requirements. Ireland satisfied EU Fiscal Compact bound on

structural deficits in all years between 2000 and 2007, with exception of two.

Of course, in all but one year over the same period, we also failed to satisfy

the very same bound if we were to use the IMF-estimated structural deficits in

place of those estimated by the EU, but that simply attests to the difficulty

of pinning down the exact value of the potential GDP, required to estimate structural

deficits. We also satisfied EU-mandated debt break in every year between 2000

and 2008. In fact, between 2000 and 2007 our debt to GDP ratio was below 40% -

the benchmark consistent with long-term compliance with the Fiscal Compact.

More than fulfilling the requirement for a 3% maximum Government deficit, Irish

Exchequer run an average annual net surplus of 1.97% of GDP, accumulating

2000-2007 period surpluses of €11.3 billion and the NPRF reserves which peaked

in Q3 2007 at €21.3 billion.

In short, the Fiscal Compact is not a panacea to our current

crisis, nor is it a prevention tool capable of automatically correcting future

imbalances, especially given the difficulty of forecasting future sources of risk.

Instead, Ireland needs a combination of institutional

reforms to enhance our domestic capacity to identify points of rising risks and

to deploy policies that can address these risks in advance. A flexible and

highly responsive early warning system, such as a truly independent Fiscal

Advisory Council, coupled with reformed Civil Service, aiming at achieving real

excellence and accountability within the key Departments and regulatory offices

can help. Furthermore, abandonment of the consensus-focused systems of

governance, eliminating the expenditure-centric Social Partnership and the Dail

whip system, and reformed legislative and executive systems to increase the

robustness of the checks and balances on local and central authorities, are

needed to develop capacity to respond to emerging future crises. Legal reforms,

to address the imbalances of power of the vested groups, such as bondholders or

state monopolists, vis-à-vis the taxpayers, are required to prevent future

bailouts of private and semi-state enterprises at the expense of the Exchequer.

Local authorities reforms are required to ensure that the madness of

over-development and land speculation do not build up to a systemic crisis.

Taxation reforms are needed to stabilize future revenues and develop an

economically sustainable tax system.

The Fiscal Compact is a wrong policy for all of the above because

it risks creating a confidence trap, which can replace or displace other

reforms. It represents a wrong set of objectives, as it diverts state attention

from considering the nature of underlying imbalances. It also re-directs much

of the fiscal responsibility away from Irish authorities, potentially

amplifying the reality gap between the real economy and the decision-makers. By

endlessly blaming Europe for tying Government’s hands, the Compact will

continue building up voters’ perception disenfranchisement, fueling stronger

local political orientation toward parochialism and narrow interests

representation, while alienating voters from European institutions.

In short, the Compact is not an end to the politics as usual.

This, perhaps, explains why no independent analyst or politician is prepared to

vote in favour of the new Treaty except under the threat of the Blackmail

Clause contained not in the Fiscal Compact itself, but in the forthcoming ESM

Treaty and which requires accession to the Treaty on Stability, Coordination

and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union as a pre-condition for

gaining access to the ESM funds. Not exactly a moment of glory for either

Europe or Ireland.

Box-out:

By now, we have become accustomed to the endless repetition

of the boisterous claims that the continued declines in Government bond yields

since mid-2011 signal the return of the markets confidence in Ireland. Alas,

based on the last two months worth of data, things are not exactly going

swimmingly for this school of thought. Based on weekly data, Irish benchmark

9-year bond yields spreads over Germany have contracted sharply in year on year

terms, falling on average 1.30 percentage points since March 1, 2012 and 1.26

percentage points in April. The former is the second best performance in the

euro zone after Italy, and the latter marks the third best performance after

Italy and Portugal. Alas, weekly changes have been much less impressive. Since

March 1, our yields have actually risen, in weekly terms, with an average rate

of increase of 0.02 percentage points. For the month of April, the same metric

stands at 0.05 percentage points. The same performance pressure on Ireland is

building up in the Credit Default Swaps markets, with our 5 year benchmark CDS spreads

declining just 0.24 percentage points compared to Portugal’s 5.2 percentage

points drop since a month ago. Overall, European CDS and sovereign bonds

markets are now signalling the exhaustion of the positive momentum from the December

2011 and February 2012 LTROs. Ireland’s bonds and CDS are no exception to this

rule, suggesting that the ‘special relationship’ that we allegedly enjoy with

the markets might be now over.