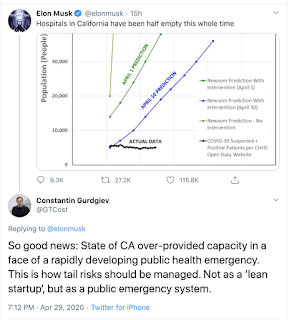

A tweet from @elonmusk yesterday has prompted a brief response from myself:

https://twitter.com/GTCost/status/1255681426445365248?s=20

For two reasons, as follows, it is worth elaborating on my argument a little more:

- I have seen similar sentiment toward authorities' over-providing healthcare system capacity in other countries as well, including, for example in Ireland, where the public has raised some concerns with the State contracting private hospitals for surplus capacity; and

- Quite a few people have engaged with my response to Musk.

So here are some more thoughts on the subject:

'Lean startups' is an idea that goes hand-in-hand with the notion that a startup needs some organic growth runway. In other words, it needs to ‘nail’ parts of its business model first, before ‘scaling’ the model up. ‘Nailing’ bit is done using highly scarce resources pre-extensive funding (which is a ‘scaling’ phase). It makes perfect sense for a start up, imo, for a startup.

But in the ‘nailing’ stage, when financial resources are scarce, the startup enterprise has another resource is relies upon to execute on a ‘lean’ strategy: time. Why? Because a ‘lean’ startup is a smaller undertaking than a scaling startup. As a result, failure at that stage carries lower costs. In other words, you can be ‘lean’ because you are allowed to fail, because if you do fail in that stage of development, you can re-group and re-launch. You can afford to be reactive to news flows and changes in your environment, which means you do not need to over-provide resources in being predictive or pro-active. Your startup can survive on lean funding.

As you scale startup, you accumulate resources (investment and retained earnings) forward. In other words, you are securing your organization by over-providing capacity. Why? Because failure is more expensive for a scaling startup than for a 'lean' early stage startup. The notion of retained and untilized cash is no longer the idea of waste, but, rather a prudential cushion. Tesla, Mr. Musk's company, carries cash reserves and lines of credit that it is NOT using at the moment in time precisely because not doing so risks smaller shocks to the company immediately escalating into existential shocks. And a failure of Tesla has larger impact than a failure of small 'lean' startup. In other words, Mr. Musk does not run a 'lean startup' for a good reason.

Now, in a public health emergency with rapid rates of evolution and high degree of forecast uncertainty, you cannot be reactive. You must allocate resources to be pro-active, or anticipatory. In doing so, you do not have a choice, but to over-supply resources. You cannot be ‘lean’, because the potential (and highly probable) impact of any resource under-provision is a public health threat spinning out of control into a public health emergency and a systemic shock.

‘Lean’ startup methods work, when you are dealing with risk and uncertainty in a de-coupled systems with a limited degree of complexity involved and the range of shocks impact limited by the size of the organization/system being shocked.

Public health emergence are the exact opposite of such a environment: we are dealing with severe uncertainty (as opposed to risk) with hugely substantial impacts of these shocks (think thousands of lives here, vs few million dollars in investment in an early stage start up failure). We are also dealing with severe extent of complexity. High speed of evolution of threats and shocks, uncertain and potentially ambiguous pathways for shocks propagation, and highly complex shock contagion pathways that go beyond the already hard-to-model disease contagion pathways.

So a proper response to a pandemic, like the one we are witnessing today, is to use an extremely precautionary principle in providing resources and imposing controls. This means: (1) over-providing resources before they become needed (which, by definition, means having excess capacity ex-post shock realization); (2) over-imposing controls to create breaks on shock contagion (which, by definition, means doing too-much-tightening in social and economic environment), (3) doing (1) and (2) earlier in the threat evolution process rather than later (which means overpaying severely for spare capacity and controls, including - by design - at the time when these costs may appear irrational). And (4), relying on the worst-case-scenario parameterization of adverse impact in your probabilistic and forecasting analysis and planning.

This basis for a public health threat means that responses to public health threat are the exact opposite to a ‘lean’ start up environment. In fact they are not comparable to the ‘scaling up’ start up environment either. A system that has a huge surplus capacity left in it, not utilized, in a case of a start up is equivalent to waste. Such system’s leadership should be penalized.

A system that has a huge surplus capacity left un-utilized, in a case of a pandemic is equivalent to the best possible practice in prudential management of the public health threat. Such system’s leadership should be applauded.

And even more so in the case of COVID pandemic. Mr. Musk implies something being wrong with California secured hospital beds capacity running at more than double the rate of COVID patients arrivals. That's the great news, folks. COVID pandemic carries infection detection rates that double the population of infected individuals every 3-30 days, depending on the stage of contagion evolution. Earlier on, doubling times are closer to 3 days, later on, they are closer to 30 days. But, utilization of hospital beds follows an even more complex dynamic, because in addition to the arrival rates of new patients, you also need to account for the duration of hospital stay for patients arriving at different times in the pandemic. Let's be generous to sceptics, like Mr. Musk, and assume that duration-of-stay adjusted arrivals of new patients into the hospitals has a doubling time of the mid-point of 3-30 days or, close to two weeks. If California Government did NOT secure massively excessive capacity for COVID patients in advance of their arrival, the system would not have been able to add new capacity amidst the pandemic on time to match the doubling of new cases arrivals. This would have meant that some patients would be able to access beds only later in the disease progression period, arriving to hospital beds later in time, with more severe impact from the disease and in the need of longer stays and more aggressive interventions. The result would have been even faster doubling rate in the demand for hospital beds with a lag of few days. You can see how the system shortages would escalate out of control.

Running tight supply chains in a pandemic is the exact opposite to what has to be done. Running supply capacity at more than double the rate of realized demand is exactly what needs to be done.

We do not cut corners on basic safety equipment. Boeing did, with 737-Max, and we know where they should be because of this. We most certainly should not treat public health pandemic as the basis for cutting surplus safety capacity in the system.